Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

a brief biography

The Legend That Was Eamonn Andrews

a celebration to mark the presenter's centenary year

the studio look and locations

Radio Times feature on the programme's chauffeur

Writes T. LESLIE JACKSON

Producer of the Famous BBC Show

THE most hated TV star in my office was "Sergeant Bilko." Because Bilko preceded This is Your Life, and the sight of his happy, carefree face laughing its way through a comedy series, while we in the TIYL team were absolutely on edge, irritated us enormously. No reflection on Phil Silvers' tremendous skill - it was just that we wished he would get off the air at that time.

Heart-stopping moments happen in nearly every edition of This is Your Life. Almost always our first reaction when the subject comes on, and the book is thrown at him, is "Help! He knows!" or "She knows!" We are terrified that, in spite of all the precautions we've taken, the subject has somehow found out about the programme. Unless they practically stand up and say, "I swear I didn't know about this before," I always think they do. But we have never yet had an occasion when this has happened. Afterwards we always ask people, "Will you cross your heart and tell us you didn't know about the show?" and they always answer, "Well, how on earth could I have known?"

There's a green book on my desk full of notes on "lives" we might do at some time in the series. At our regular Tuesday morning meetings Eamonn Andrews and I decide which particular line shall be taken. We discuss the previous night's programme, final details of the one for the following week, the story line for the one after that, and whose story is to be tackled after that.

Because of the nature of This is Your Life this four-weekly pattern is an ideal which doesn't always come off. Sometimes we are not happy with the story line, or we find the subject is not available; the plan might be altered twice in a week. One programme you saw was in fact our sixth attempt at finding that week's subject! Thus, whereas sometimes we have three weeks in which to prepare, at other times we may have only a couple of days before the show.

After the script is completed my team works on the final plan to get the subject to the studio. This is done in various ways; perhaps by inviting him to a telerecording for another show, or for some public appearance.

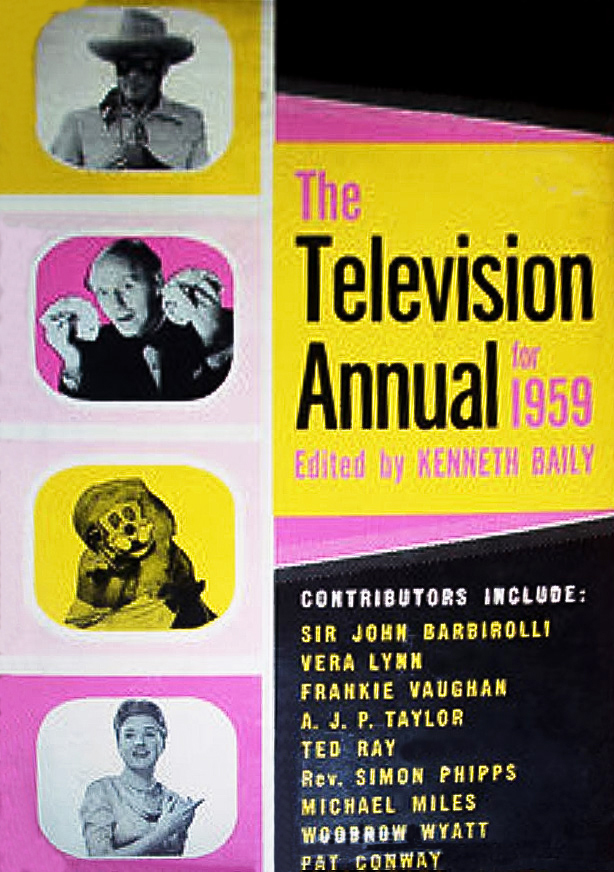

Praised, and also criticised, for being a "tear-jerker," This is Your Life has rarely succeeded in releasing as much emotion as when Anna Neagle was its subject. She cried. But this was a calmer moment in the programme, when Frankie Vaughan joined her

It was impossible to bring Anna Neagle to the Television Theatre, for instance, so Picture Parade handled her for us. They signed letters (which we wrote) saying they were interested in her new career as a film director. Would she mind if they interrupted one of her directing sessions and talked to her actually on the job? That's what happened - except that it wasn't Picture Parade!

That was one of the most nerve-racking programmes I've done, because we had to have our cameras in the film studios watching Anna for a good half-hour before we went on the air. She knew we were recording part of her film rehearsal, but I was afraid that at any moment she might decide to call off the rehearsal, have a break or otherwise disappear at the vital time. Luckily she stayed there; but to have to sit and watch your subject like this for half an hour is a refined form of torture.

She was grateful afterwards - even though she had wept copiously. And if anyone says we showed bad taste in putting on that film of the late Jack Buchanan which caused Anna to break down, I would like them to tell me how we could have thought of showing Anna Neagle's life without him. We gave the matter a tremendous amount of thought; and Anna said afterwards, "I am so glad you included Jack."

Perhaps the most legendary editor of modern Fleet Street, Arthur Christiansen (right) of the Daily Express had his electrifying career probed by This is Your Life. Sir Leslie Plummer, M.P., recalls incidents in Christiansen's life, while Eamonn Andrews and Francis Williams (seated) listen

A timing error almost killed the programme on Arthur Christiansen, the famous editor of the Daily Express. We had him picked up by car to come to Lime Grove to meet a BBC official. He was brought to Shepherds Bush by a driver who pretended to be unsure of the way, and went the wrong side of Shepherds Bush Green. It was pointed out by our confederate in the car that Lime Grove was a one-way street, but that he could turn to his left down Pennard Road. There we had a parking place fixed at the back of the theatre where we do the programme, and at that point the car was to be stopped by Eamonn Andrews.

For the first time in all the many jobs he's done for us, driver Danny Roman's timing went wrong and he got there one minute too early. While Eamonn Andrews was introducing the show on the stage I on my preview screen saw the car go past in the road behind the theatre! I thought the driver was going on round the block and back down the road, which would have been nice timing. Instead of doing this, however, he panicked, went on a longer time-killing circuit and arrived three minutes too late. I went through agonies during that time, not knowing whether he was going to come back at all!

One of the first programmes we gave was on the Rev James Butterworth of London's Clubland. The great thing in Jimmy's Clubland life is a big service he calls "Sunday at Seven." Our programme in those days was screened on Sunday at 7.30. We had to get him away from Clubland by seven o'clock, and we could not expect to pick him up just as he was going into his service, so we had to catch him earlier. We arranged for one of his Clubland trustees to go along at 6.15, meet him there and say:

"I want you to do something special for the good of Clubland. I don't want to tell you what it is. Will you trust me?"

"Of course I will," said Jimmy. "What is it?"

"I want you to come with me to a meeting-place now."

"How can I? I've got to take my service at seven."

At this point the boy who reads the lessons at the service, and who was in the secret, stepped forward and said:

"Please, Mr Butterworth, this is an opportunity I've always wanted. I'll read the lessons. I've always wanted to take the service. Give me this chance."

Jimmy rather hesitatingly agreed to let him do it, and was then taken out. We then had the problem of delaying his arrival for an hour. He was taken to another trustee's house; this man was included in the party and talked to him all the way to Lime Grove. Again we started without knowing exactly where our subject was. After Eamonn had spoken to three people in the audience Jimmy was to come through the theatre door, having been met on the steps by Jerry Desmonde, whom he had previously met many times with Bob Hope. Our eyes were fixed on that door while outside Jerry was saying, "I've got a little scheme in here to help Clubland - come in with me." Once Jerry had met him, of course, everything was all right.

The programme on Louie Ramsay, the young actress who had shown such promise before suddenly being paralysed in the feet, gave us a lot of excitement After a year of splints and hospitals she fought back, threw off her affliction and made a come-back in pantomime at the King's Theatre, Edinburgh. We decided to interrupt the performance, and told the management and staff that the BBC was doing a show called Panto Story and we were filming excerpts from three pantos.

We had no worry about our subject because she was on the stage, but we let into the secret the theatre manager, lessees, producer and stage-manager. We wanted to take in the finale of the first half, in which Louie appeared twice. We hoped the timing would allow us to pick her up the first time. But it wasn't quite 8.15, and Sergeant Bilko was still on the screen! This not only gave me a scare, but cost us £300; because in the first part she was on stage with five people only, but in the second she appeared with the whole company and I had to pay every single one for appearing on television!

Another worry about that show was that I had to take the risk of someone in the Edinburgh theatre audience saying, "What is this? I didn't pay to see This is Your Life, I paid to see a pantomime. I object..." And we would have had to stop it. However, it came off all right.

Sometimes we are criticised for bringing tears to television. But they are honest tears, tears of true emotion if people like it, and very often tears of joy. I had a letter from a little girl after our programme last Christmas on Mrs. Dobson, a dear old lady. The little girl wrote: "My mummy likes your programme but I don't because you make old ladies cry, and this old lady was crying at Christmas and I think you're very cruel."

I wrote back to her saying when she grew older she would know that sometimes if you're very happy, you cry instead of laughing. And that if she could have seen Mrs. Dobson twenty minutes later tucking into a Christmas dinner I was sure she would have been very happy, too.