Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Bob HOPE (1903-2003)

- The Big Red Book is first seen - ironically in black and white due to a technician's strike

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Bob Hope, actor, comedian and entertainer, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at Thames Television's Euston Road Studios, having been led to believe he was there for an interview with Eamonn for the Tonight programme.

Bob was born in London but moved to the United States as a child when his family emigrated there in 1908. After deciding on a show business career, he spent several years on stage as a dancer and comedian in vaudeville before first appearing on radio in 1934. His radio and vaudeville appearances attracted the attention of the movie business, and after moving to Hollywood in 1937, he made his first feature film appearance in The Big Broadcast of 1938.

Along with Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour, he starred in the highly successful 'Road' movies during the 1940s, as well as many other films and several television specials from the early 1950s. During the Second World War and the Korean and Vietnam wars, Bob travelled more than a million miles on every battlefield to entertain the US troops.

Bob Hope was a subject of This Is Your Life on two occasions - surprised again by Michael Aspel in August 1995 at the CBS Studios in Los Angeles, California - in a joint tribute with his wife, Dolores.

"Come on... you're kidding!"

programme details...

- Edition Nos: 283 / 284

- Subject No: 285

- Broadcast date: Wed 18 Nov 1970

- Broadcast date: Wed 25 Nov 1970

- Broadcast time: 7.00-7.30pm

- Recorded: Tue 17 Nov 1970

- Venue: Euston Road Studios

- Series: 11

- Editions: 1 - 2

- Code name: Charity

on the guest list...

- Walter Annenberg - live link

- Tony Bennett

- Frank Symons - cousin

- Kathleen Symons

- Jean Nixon - in audience

- Maurice Nixon - in audience

- Mrs Tom Simons - in audience

- Dr Roger Phillips - in audience

- Mrs Roger Phillips - in audience

- Philip Briers - in audience

- Mrs Philip Briers - in audience

- Rev James Butterworth

- Mildred Rosequist

- Dolores Hope - wife

- David Frost - via radio telephone

- Tommy Trinder

- Ted Ray

- Ray Milland

- Gen Emmett 'Rosie' O'Donnell Jr

- Joan Rhodes

- Denis Goodwin

- Nora - daughter

- Linda - daughter

- Tony - son

- Kelly - son

- Lord Mountbatten Filmed tributes:

- President Richard Nixon

- Jack Benny

- Dorothy Lamour

- Bing Crosby

related appearances...

- Joe Brannelly - Jan 1956

- David Frost - Jan 1972

- Eamonn Andrews - May 1974

- Ted Ray - Feb 1975

- Ray Milland - Nov 1975

- Louis Mountbatten - Apr 1977

- Bob Monkhouse - Feb 1982

- Diana Dors - Oct 1982

- Jimmy Tarbuck - Apr 1983

- John Mills - Oct 1983

- Alice Faye - Dec 1984

- Henry Cotton - Feb 1986

- Teddy Johnson and Pearl Carr - Nov 1986

- Bill Ward - Dec 1986

- Dudley Moore - Mar 1987

- Mickey Rooney - Oct 1988

- Zsa Zsa Gabor - Nov 1989

- Douglas Fairbanks Jr - Dec 1989

- Brian Conley - Nov 1995

- Bob Monkhouse - Apr 2003

production team...

- Researcher: Alan Haire

- Writer: John Sandilands

- Director: Margery Baker

- Producer: Robert Tyrrell

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

second tribute

Hollywood in the spotlight

surprised again!

two's company

keeping it in the family

the programme's icon

the studio look and locations

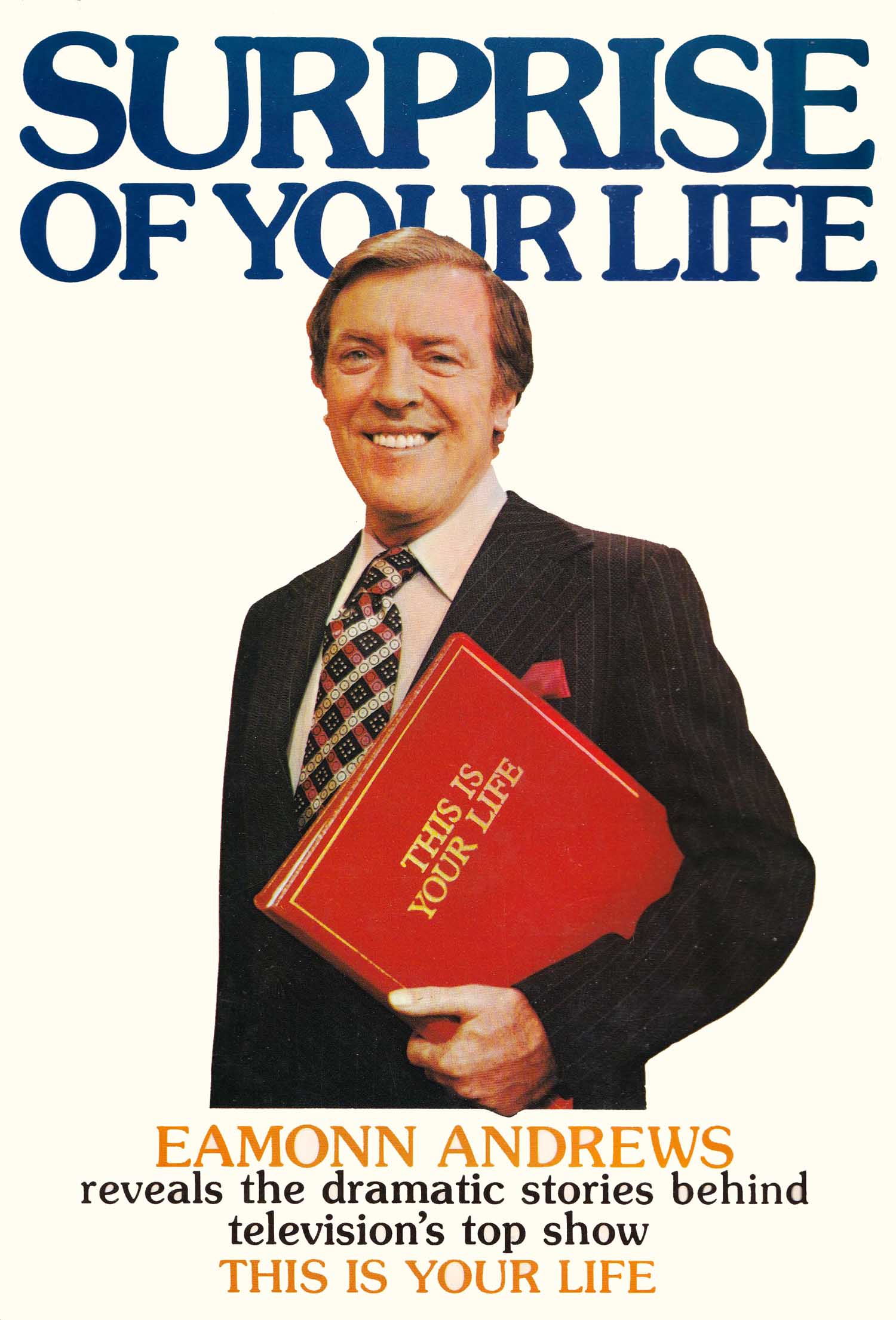

tributes to the original presenter

the show's fifty year history

TV Times takes a light-hearted look at keeping a secret

The secret life of Eamonn Andrews

Weekend Magazine feature on the show's popularity

Ratings slump sounds death knell for This Is Your Life

Press speculation on the future of This Is Your Life

Screenshots and photographs of Bob Hope This Is Your Life

I was in my dressing room, just a few yards along a narrow corridor from the This Is Your Life studio, dotting the i's and crossing the t's of my script when a call came through, telling me Bob Hope was going to be delayed.

It was the first of a succession of calls that filled the next hour with suspense.

Sixty minutes seemed like sixty long days as we waited for Bob to walk unsuspectingly into our trap.

Months before, when we had heard that he was to fly from his Hollywood home to London for a charity concert, we had moved in quickly to book him for "an interview". It had all been done officially and efficiently. A call from a producer at Thames to Bob's London agent. A call from the agent to Bob to check his availability. Then written confirmation.

What Bob didn't know, of course, was that his wife, Dolores, had already received another telephone call from Thames Television – to discuss Bob's life. And when the couple boarded the jet to fly to England together only Dolores knew how the interview was going to turn out.

But now, as we anxiously waited, Dolores Hope began to lose her nerve. And she wasn't the only one. She joined me in my dressing room for a chat and a steadying drink before the next phone call came through telling us that Bob was still involved... at, of all places, the BBC.

To fit our plan of surprise, he had been asked to come to Thames one hour before the scheduled interview. Being the seasoned pro he was, and being so experienced at this sort of thing, he would know that it would be possible in fact to arrive only a minute or two beforehand.

But what he certainly did not know and what no one could tell him was that we had elaborate plans that were geared to a very tight schedule. Among these plans was a live link from our studio to a palatial house in Regent's Park. Bob had been voted by the American Congress "America's most prized ambassador of goodwill" and was a good friend of the American Ambassador to Britain Mr Walter Annenberg. So we had approached Mr Annenberg to make a personal contribution to the programme.

He agreed without hesitation. But then we discovered a snag. The night of our programme was the night the Ambassador to the Court of St James, to give him his official title, was hosting a huge banquet at home for a guest list that included members of the Royal Family.

Disappointed that he couldn't come to the studio he agreed to allow us to put cameras in his home so that he could talk to Bob via a live link during the programme. But there was one condition. The cameras, cables and their attendant technicians would have to have finished before his first guests arrived for dinner.

In fact, they almost did better than that. During a break in the preparations, John Sanders, our floor manager, took the weight off his feet, sat back on one of the ambassadorial chairs and stretched himself. All Hell broke loose! His head had gently tapped a valuable painting behind him and triggered off a security alarm.

I gather that gentlemen with bulges in their pockets seemed to come out of the woodwork before peace was finally restored. The crew waited for the countdown to the programme – standing.

Back at the studios, the next call came through, this time from a radio car we had hired to tail Bob as he left the BBC studios en route for us. The driver told us that Bob was on his way, more than half an hour behind schedule and in very heavy traffic.

While Dolores and I chatted, another comedian, Denny Piercey, was working overtime in the studio. Denny regularly helps us out as audience warm-up man. The comic whose job it is to make sure that the audience, most of whom have never been in a television studio in their lives, feel at home.

And he does his job in the most expert way. A joke here, a joke there, an introduction to the studio crew, an explanation of the way we work. All aimed at keeping everybody in a happy mood for the programme.

Normally he's up there on his feet for about ten to fifteen minutes before we start. Fortunately, like all good comedians, he has a never-ending list of gags. And I think that that night the audience heard most of them.

Up above him in the control box the studio director, Margery Baker, relayed a running commentary, using information gleaned from the car radio phone to explain the delay to Mr Annenberg and his staff over the live link.

Downstairs in the "Green Room" other members of the team were busy doing what I was doing, steadying the nerves of the guests. The Green Room is the room we have set aside from the studio to welcome the guests and offer them controlled measures of "hospitality" – tea, coffee or sometimes even stronger. While one of Bob's English-born realtives from Bristol sipped tea, I seem to remember singer Tony Bennett settling for the something stronger served up by the Green Room "mine host", Reg.

All the guests were locked in to avoid being spotted before the show. It's all part of a pre-show security routine that would do credit to the Bank of England or, in this case, Fort Knox. A routine that results in guests sometimes being accompanied even to the loo, so that they don't turn a wrong corner and risk bumping into the wrong person.

On one occasion, one of the team's new secretaries spotted a face she didn't recognise peeping around the Green Room door. She quickly accosted him and asked if he was a guest. When he said he wasn't she politely banned him from the room. We were all glad she had been polite, for the stranger turned out to be none other than Mr Howard Thomas, the managing director, now chairman, of Thames Television. Fortunately, being a former producer who knows television inside out, Howard was most impressed.

Perhaps one of the most soothing places during a waiting crisis is a room just around the corner from mine. It's the make-up department and though I would never have thought it in my days as a boxer, a dab of powder on the nose and forehead, skilfully applied by our own Mimi or Jeannie, can do wonders to relax you in those tense moments before you face the cameras.

In there was Bob's daughter, Linda, who the day before, was involved in an amazing double coincidence that nearly lost us the show. After we had secretly flown her from Los Angeles to surprise her Dad she made a swift sortie from her hotel to visit a hairdressing salon in the West End.

Coincidence number one came the moment she walked in through the door to spot Tina, Frank Sinatra's daughter.

Coincidence number two followed only minutes later when the famous twosome were recognised by a sharp-eyed Fleet Street photographer, quick to realise that he had a nice little scoop in his lens. Snap, and he was on his way back to his office. Click, and Linda realised the danger.

If the picture was published and seen by Bob he would want to know what Linda was doing in London when he thought she was at home in the United States. There was only one thing to do: take the newspaper totally into our confidence by telling them the secret we had been sitting on for so long. Sportingly, they agreed not to publish the pictures and risk spoiling the pleasure for millions of viewers.

When Bob did eventually arrive an hour late there was another picture I was glad he didn't see. After I had surprised him in the foyer I took him straight into the studio, sat him down and, before the audience applause had died down, I had opened the story. I knew that, among many pressing problems now upon us, we not only had to get the cameras out of the Ambassador's dining room but one of our guests now hiding behind the set was also one of Mr Annenberg's guests of honour. Making his first appearance on This Is Your Life it was no less that Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Having met him before I knew him as a man who knew his own mind, didn't have to raise his voice but made you know damned well what he wanted when he said so. He is also a man who prides himself on his punctuality. And now, through no fault of his own, he was in danger of being late for an important engagement.

I pressed on with the show introducing an array of star guests, friends and relatives. There was even a filmed message from the President of the United States. As we neared the climax, on came Bob's youngest son Kelly who had cut short an educational cruise aboard a ship to fly in from Dubrovnik in Yugoslavia to complete the family.

Then, out of the corner of my eye, I could see Lord Mountbatten waiting in the wings. I could also see our stage manager, Roy Fewins, almost struggling with him. I could visualise the conversation. In fact I felt that I could almost hear Lord Louis saying that he was so late that if he didn't get on now he would have to leave. And at that very moment I saw Lord Louis actually pop his head around the door at the back of the set.

Fortunately, Bob wasn't so well placed and missed the picture which, on reflection, I suppose was quite amusing. Moments later, of course, Bob was delighted when he shook hands with Lord Louis and thanked him wholeheartedly for joining in the tribute.

A telephone call wiped the smiles from our faces as we prepared to pounce on the legendary British-born comedian, Bob Hope.

It was from his wife, Dolores. We had flown her in, with their four children. And daughter Linda was the subject of the call.

She had visited a West End hairdressing salon where she had bumped into, of all people, a Hollywood friend – Frank Sinatra's daughter, Tina. A newspaper photographer was there to picture Tina. Now, right out of the blue, he had the chance to photograph the daughters of the two international stars together. Only after he had gone did it dawn on Linda that if her father saw that picture published he would know she was in London, and would want to know why.

No wonder we weren't smiling. We decided there was only one thing to do – take the newspaper into our confidence, with the promise of exclusive coverage on the night in return for publication of the photo being delayed until after the programme.

Another argument was simply why spoil the surprise for millions of viewers – and newspaper readers – for the sake of a headline? I have always thought that counter-productive.

The paper agreed, so we were able to go ahead with our surprise, but not without more behind-the-scene jitters. The great comedian had been booked for a non-existent interview on the Today programme at the Euston Road studios of Thames Television, where we planned to surprise him, on 17 November 1970. But he was detained at, of all places, the BBC. He was not aware, of course, that we were running to a very tight schedule because we had outside broadcast cameras in Regents Park, at the residence of the American Ambassador to Britain, Walter Annenberg.

The idea was for the ambassador to make a live contribution to our programme, congratulating Bob Hope on being voted 'America's most prized ambassador of goodwill' by the American Congress.

Mr Annenberg was about to host a banquet, with guests including members of the Royal Family, so by running late at our end we were sorely trying his goodwill.

The situation was not helped by a member of the outside broadcast team accidentally leaning his chair against an extremely valuable painting, setting off the alarm system: the resultant security alert just added to our problems.

What is more, we were detaining one of Mr Annenberg's VIP guests – Lord Louis Mountbatten. He kept consulting his watch as I made small talk with him in the Green Room. It was clear if something did not happen soon the Admiral of the Fleet would be full steam out of the place.

At last, Bob sauntered into the studio foyer with that familiar casual air. Eamonn shed the panic of the last hour and feigned a similarly casual air as he approached to tell Bob it wasn't going to be an interview at all, but This Is Your Life.

Back in the Green Room Lord Louis, a stickler for military punctuality was by this time champing at the bit. Quickly, he was taken backstage for his surprise walk-on. So keen was he to get on – and off - that he popped his head around the door at the back of the set. The audience spotted him, but Bob did not. The stage manager had to restrain him. Then on he came to thank Bob Hope for his ceaseless charity work, and one legend was clearly much flattered by the presence of another.

Quite a few more legendary faces were on that programme, including Dorothy Lamour and Bing Crosby, Gregory Peck, Arnold Palmer, Sammy Davis Junior and John Wayne.

Mr Annenberg said his few words and the outside broadcast team cleared their lights, cameras and cables away in the nick of time, just as the banquet guests were arriving – including Lord Louis, punctual to the second.

Once he used Today as a means to trap one of his favourite comedians, Bob Hope. Eamonn gave the impression to the comedian's Hollywood agent that he wanted to interview the star on the magazine programme when, in fact, he hoped to surprise him for This Is Your Life. To Eamonn, Hope was one of the all-time great comics; he loved his spontaneous one-liners; he happened also to like the man himself, which in Eamonn's case was always important. They had already met in Hollywood and privately Eamonn had vowed that one day he would hand him the red book.

Now, as he waited in his dressing room he was told that Hope was delayed. 'Sixty minutes seemed like sixty long days as we waited for Bob to walk unsuspectingly into our trap,' he recalled. Months before he had 'booked' him for the Today 'interview', and Bob Hope's wife, Dolores, had agreed to be an accomplice in the plot. Now she was in danger of losing her nerve. Eamonn offered her a drink and they chatted anxiously as the minutes ticked away. Another phone call came through to say that the comedian was held up in heavy traffic. Eamonn sighed and looked at his watch - there was only half an hour remaining to the start of the Life programme. Meanwhile, a warm-up comic was keeping the audience in a happy mood. All the guests were locked in to avoid being spotted before the show. In there was Hope's daughter, Linda, who the previous day had met Frank Sinatra's daughter Tina at a hairdressing salon in the West End and a short time afterwards they were spotted by a Fleet Street photographer who snapped them for an evening newspaper. As Eamonn recalled 'if the picture was published and seen by Bob Hope he would want to know what Linda was doing in London when he thought she was at home in the States. There was only one thing to do: take the newspaper totally into our confidence by telling them the secret we had been setting up for so long. Sportingly they agreed not to publish the picture and risk spoiling the pleasure of millions of viewers.'

When Hope did eventually arrive an hour late he was immediately surprised in the foyer by Eamonn and guided directly into the studio. Although obviously amazed to be met by the applause of an enthusiastic audience, the famous comic took it all rather philosophically, smiling as Eamonn introduced a galaxy of stars, among them Tony Bennett and Dorothy Lamour.

Waiting in the wings was Lord Louis Mountbatten, who was eager to get on with the show as he had an urgent dinner engagement. Eamonn could almost hear him say that it was so late that if he wasn't soon called in to pay his tribute he would have to leave. It was his first time on the Life programme.

...I left England when I was four because I found out I could never be king.

CUE IN

"This Is Your Life, Leslie Towns Hope!"

New York, Sunday, November 15, 1970

There had been rain since early morning. It was raw and windy weather but the planes were flying at Kennedy. The Hopes were headed for London where Bob would entertain royalty twice in five days. As usual they were running late, and the passenger agent worked fast to hustle four hefty pieces of luggage, including Bob's theatrical wardrobe trunk, to the plane.

The airline had been alerted. Even before the limo had time to glide out of the Waldorf driveway, an assistant manager standing in the Towers lobby was on the phone asking a BOAC official to hold the London flight. Somehow, they arrived at Kennedy with minutes to spare.

Hope breezed through this barely-making-flights routine with an accustomed nonchalance that could have been irritating to the airlines except that he was a unique customer. After all, for thirty years his benign airline gags ("I knew it was an old plane when I found Lindbergh's lunch on the seat"), and his omnipresence in airports and on regularly scheduled flights (sometimes he racked up as many as 20,000 miles a week), rendered him a cherished unsalaried spokesman.

He was striding now a few feet ahead of Dolores toward the gate, affably smiling at people who stopped in disbelief. He spotted a public telephone, and while the passenger agent escorted Dolores to the plane, Bob called "the boys" on the Coast.

It was one of his celebrated NAFT calls, the writers' acronym for "need a few things" at whatever hour and from whatever place. Usually he called his chief writer and television producer Mort Lachman who, then, called the other six. Right now Hope needed Grace Kelly material because she had, on very short notice, replaced an ailing Noel Coward as compere (British for master of ceremonies) of his Monday night London benefit. Also, he had neglected to tell Mort he would be staying at the Savoy this trip.

The passenger agent hovered over Hope and was visibly relieved when the comedian finally hung up. By now his telephoning had delayed the takeoff. Hope walked briskly into the first-class section of the plane, humming and smiling his way to what was universally acknowledged as "his" seat on any commercial flight - the right-side bulkhead seat. There he could stretch out, put his feet up, work undisturbed. And when he traveled alone, which was more often than one might suspect, the airline thoughtfully left the space beside him unsold.

Soon after takeoff, Bob opened his briefcase, put on his half-glasses and began to look over the London material that Miss Hughes had put in his case. On top were fact sheets prepared by his public relations people describing the royal events and Hope's role in each one.

Dolores glanced down and followed with interest the details of his Monday night benefit performance, extravagantly labelled "A Night of Nights." It was a fund-raiser for Louis Mountbatten's favourite charity, the United World College Fund, for which Bob was sharing the bill with Sinatra.

Two identical performances were scheduled back-to-back for Royal Festival Hall audiences expected to pay £50 a ticket. The first of these two shows would be videotaped by BBC for international distribution, and Hope was concerned that his first audience might be a tougher one to reach. He would prefer BBC to tape the second show - or both, for that matter - because he had some special material he could "try out" on the first sitting.

Following the second performance, he and Dolores, Sinatra, Princess Grace, and assorted other members of the British elite were invited to a buffet supper at St. James's Palace hosted by Prince Charles and Princess Anne.

This event held particular interest for Dolores, as well as a certain amount of disappointment. While she and Bob were dining with the royal family, the rest of her immediate family - daughter Linda and husband Nat, daughter Nora and husband Sam, son Tony and wife Judy - would be lurking at the Savoy and forced to dine wherever they could remain anonymous. Yet, Dolores appreciated the importance of these cloak-and-dagger arrangements. They related to Tuesday night's surprise event.

The Hope children, including son Kelly if he could be located, were being flown to London to surprise Bob in Thames Television's production of This Is Your Life. Hope was to be the first honoree in a British revival of the American radio-television success show of the early fifties. Dolores was pleased that this secret had been successfully kept from Bob, who generally hated surprises but mysteriously seemed to know everything that was going on. What convinced Dolores that the secret was intact was a conversation she and Bob had a few days before.

"Bob, be sure and have Miss Hughes add the Annenberg dinner party to your London schedule. It's Tuesday night. They're honouring Mountbatten."

"When is it?"

"It's Tuesday."

"What time Tuesday, Dolores? I'm taping a talk show at Thames Television that night."

"It's dinner. I think seven."

"I can join you there. I should be finished by seven-thirty."

Dolores had studied his face; she was positive he didn't know. If the surprise was to be tipped off, it would happen because the Thames producer had arranged, foolishly in Dolores' view, to house all of the "Life" show guests at the Savoy. Program coordinator Alan Haire confidently assured her that precaution had been taken - whatever that meant - to protect Hope and the guests from meeting each other prematurely.

Actually, Dolores felt secure about most of the arrangements for this London trip. This was largely due to the numerous telephone calls she had received in recent weeks from Lady Carolyn Townshend, Bob's socially prominent London press agent, whose sometime royal connections were useful in coordinating these high-level engagements, making wardrobe suggestions and smoothing out questions about protocol.

London, Monday afternoon, November 16, 1970

Carolyn arrived at the Savoy just after one o'clock. It was sleeting when she stepped out of the cab and she nearly lost her umbrella in a sudden gust of wind. She pulled off her rainhat and looked around the lobby. The cherubic Denis Goodwin came to greet her.

"He's not taking calls according to the operator," said Denis.

"The hell," she said, with a desperate look on her face, as she headed for the house phones. The operator agreed to connect her with Hope only after she imperiously announced "This is Lady Carolyn Townshend" in her well-bred voice.

Hope responded sluggishly, asking what time it was. "It's one o'clock, Bob." she said. "And we're due at Festival Hall in forty-five minutes." He told them to come upstairs. Dolores had gone out to shop in Lower Bond Street. Bob was coming out of a heavy sleep. The blackout shades were still drawn and the room was stygian.

"What time is it?" he asked from his bed.

"One twenty-five," Denis said.

"What's the weather?" Hope asked, rising out of the bed and going into the bathroom, leaving the door ajar and relieving himself noisily. Denis told him about the sleet.

Breakfast arrived with amazing speed but Hope was on the telephone speaking in low tones. He hung up the phone and sat drowsily on the edge of the bed pouring coffee. The phone had rung again. This time he spoke soothingly to Charlie Hogan's wife, Pat, in Chicago. Charlie was dying of cancer. Hogan, one of Hope's two or three most cherished friends, was the booking agent who gave him the job that saved his life in 1928, and he had remained one of his agents and a confidant since. Bob told Pat that he would come to Chicago as quickly as he could, probably Saturday night at the latest.

"Denis, ask Carolyn if she wants some coffee."

Denis went into the sitting room and spoke to Carolyn who was on the other phone, then he came back. "She says no, Bob. She just wants you to hurry."

The phone rang. It was Lew Grade welcoming him to London. It rang again. It was Walter Annenberg welcoming him to London. Denis brought in a telegram that had just arrived:

BOB HOPE SAVOY HOTEL WC2 - BOB OF BURBANK

WELCOME TO LONDON - MOUNTBATTEN OF BURMA.

Hope looked through a few other messages and placed them beside his telephone.

London, Tuesday morning, November 17, 1970

Mildred Rosequist Brod - Mrs. John Brod - was awake at seven-thirty and dressed by eight-fifteen. Her breakfast tray arrived at eight-thirty. The Thames limousine was to pick her up before nine-thirty. Alan Haire had advised her that it would be a long day of sitting around the studio.

She had come to London alone, which was a big mistake. But her husband was not living with her at present, and when she had agreed to appear on the program she had been told that Bob's older brother Fred and his wife LaRue from Columbus would also be in London for the telecast, so she would have company. Mildred had known the Hopes since childhood days in Cleveland. Mildred was Bob's first sweetheart and his first dancing partner. Bob had proposed to her in front of Hoffman's Ice Cream Parlor on Euclid Avenue. They had dreamed together so many years ago of dancing their way to stardom like the Castles.

Mildred had arrived in London on Sunday, was met at Heathrow by a Thames representative and driven to the Savoy. At the hotel she learned that Fred and LaRue were not expected. As she was somewhat frightened of London, she had remained alone in her room.

Now, while she waited for the telephone to ring and announce her limo, Mildred picked up the Daily Telegraph and worked her way back to the entertainment page. There was a review of the "Night of Nights" benefit.

She was struck by the way the story seemed to focus on Sinatra and Kelly.

Finally, the telephone sounded, her limousine from Thames was waiting. She reached for her raincoat, umbrella and scarf and headed for the lobby.

Later that morning, November 17, 1970

In spite of the hour that Dolores finally got to bed, she was up, drank her hot lemon juice, was dressed and had the remainder of her breakfast by nine.

She barely glanced at the morning papers on her tray, but she had seen enough to be irked by the inordinate fuss over Grace Kelly and Frank.

She had a full day ahead of her. She had remembered to tell Bob, before she retired, that she would be out shopping and running errands all day. She assured him that she would be dressed and waiting when he returned from his Thames talk show. Secretly she had arranged to dress for the telecast in Nora's room, and the limousine would pick her and the children up at the Savoy between four and five o'clock.

Before she went out, Dolores went to Bob's door and listened, but hearing nothing, she left quietly.

Bob opened his eyes about noon and in the darkened room continued to doze for another thirty minutes. He fumbled for the phone, ordered breakfast and asked to have all the national dailies delivered to his suite. Then he got out of bed, padded to the door of his room, opened it and called out,

"Dolores?" No reply.

He was proud of her, the way she was carrying off her This Is Your Life smokescreen. She would not like knowing that he knew about it. He had, in fact, known for days. One of his publicity men had asked Miss Hughes and she had said, "You know Mr. Hope hates surprises," and so Bob was told. He had done his best to let Dolores think she was a good actress. He wondered about the rest of the cast Thames had assembled in London, besides Dolores.

His brothers Fred and Jim? The children? His relatives from Hitchin? Crosby and Lamour? Benny? If he were producing his own "Life" he would get Arnold Palmer and Frances Langford, Colonna and Durante, Merman and Lucy Ball. Of his many writers probably Hal Kantor, Larry Gelbart, Charlie Lee. And he could envision people like Westmoreland and Honey Chile. When he thought about some people who ought to be there, he felt sad remembering they were gone - Doc Shurr and Monte Brice, Charley Cooley and his brothers Jack and Ivor. Now, in Chicago, that beautiful little Charlie Hogan was slipping away.

Breakfast arrived and with it came the newspapers and Denis Goodwin, ready to work on material for his Wednesday, Thursday and Friday appearances.

"Have you looked at the papers yet?"

"Some," said Denis.

"Well?" asked Hope pouring himself half hot coffee and half hot milk. "Were we a hit?"

"Yes except in the Daily Mirror which goes bonkers for Sinatra," Denis said holding up the tabloid and turning to page three of the November 17, 1970, issue:

The simple happy truth is that, if this really was a "Night of Nights" at the South Bank's Festival Hall, then it was due entirely, well almost entirely, to the indestructible Francis Albert from Hoboken.

At that moment the telephone rang in Hope's bedroom and he went in to answer it. Denis could hear Bob reading excerpts from the Mirror article to whoever was on the other end. Hope came back to get more coffee.

"That was Mort. He's going to call back later with more stuff for the Wildlife show."

The day wore on with Hope remaining in his pyjamas, nibbling fruit and drinking orange juice, working on material and talking to people in various parts of Britain and America. He brightened considerably when a small, richly wrapped package was delivered to his suite. The stationery crest on the accompanying card had "Broadlands, Romsey, Hampshire" engraved just below it. The note read:

My dear Bob,

I am writing to thank you for your splendid generosity in making the "Night of Nights" such a tremendous success, and particularly for doing two shows in one night under the duress of the Bengal Lancers!!

You were magnificent and everybody loved your performance.

I am looking forward to seeing you again tonight when I can express my thanks and appreciation in person.

Meanwhile will you please accept this small souvenir of the "Night of Nights." The box was designed by my son-in-law, David Hicks.

Yours ever,

Mountbatten of Burma.

Hope read it aloud to Denis, and then opened the box to find a pair of exquisite cuff links in gold. He walked over to the window and looked closely at his gift.

"Who needs the Daily Mirror?" he purred.

That same night, November 17, 1970

The surprise cast of immediate family, Hitchin relatives, old friends and casual acquaintances chatted nervously in the Green Room. About 200 people sat impatient and mystified in audience seats facing a living room stage set. An anxious program host, Eamonn Andrews, had to mollify both Green Room guests and his studio audience with assurances that Bob Hope would at any moment walk through a side entrance (they would see it on studio monitors) and then step into the set believing he was the interview subject of a talk show.

Mildred Brod had been sitting around Thames studios nearly eight hours waiting for this moment and she was not particularly thrilled. One by one the guests had trickled in, but none until early afternoon. First to arrive were the Hitchin relatives, followed by other British guests, and finally by Dolores, the children and other American guests. When the room was full and there seemed a common purpose in the air, even Mildred's excitement rose to the occasion.

Hope was met outside by a Thames page and led to a particular stage door. When he opened that door, Andrews was waiting on the other side, a camera pointed, its red light glowing.

ANDREWS: Bob - you're late. How are you? There's an audience waiting for you -

HOPE: What?

Hope sounded incredulous, and stepping toward the brightly lit stage area, he removed his coat, beaded with wetness from the rainy night outside. One more step to the set; there was noisy, prolonged applause. He was dressed for the Annenberg party. He shaded his eyes to search out the audience, nodded to their greeting. He cut a dignified figure as he walked to the seat of honour.

He crossed his arms over his chest and looked up at Andrews who waited for the applause to stop.

ANDREWS: Bob, this is a very special week for you, and this is a very special time, and we want to make this a night you're going to remember for a long time - because tonight Bob Hope - this is - your life!

HOPE: Come on - you're kidding - really?

Hope looked around. He grinned like a small boy. The audience was once again applauding and a lush, symphonic version of Hope's theme song, "Thanks for the Memory," filled the studio. Andrews opened his big red book. He explained that the first guest was someone Bob would be seeing later that night. The figure who appeared on the studio monitors was Walter Annenberg, ambassador to Britain, being picked up by remote cameras as he stood in the doorway of his Regent's Park residence. Annenberg said his real task was to introduce yet another "surprise guest," Richard Nixon. The President's face, on videotape, loomed large on the monitors.

NIXON: America owes a great deal to Britain... our common law... our language... and many of our political institutions... but we are particularly indebted to England for giving us Bob Hope. Not only because he is a great humorist who has given joy to millions of his fellow citizens and countless millions throughout the world... but because he is a fine human being who has never failed to respond in helping a good cause, any place in America or in the world. We are proud to claim him as an American citizen... and I am proud to know him as my friend.

Hope seemed embarrassed, touched. This did not seem the time for one of his Nixon gags. Hope sensed the moment needed a laugh, but he was at a loss. Then a slide showing the house at 44 Craighton Road flashed on the screen, and Andrews said it was where Hope was born at Eltham.

HOPE: And we still owe some rent there.

He had found the laugh he needed and the audience responded. Then Andrews said that the baby born there was christened Leslie but the name was changed later.

HOPE: Well - I thought - Leslie - you know - might be misinterpreted, Leslie's also a girl's name. I thought Bob was more chummy and I was going to play a lot of vaudeville and I might get up on the marquee quicker.

The audience laughed again, and Hope's name-change humour led nicely into Andrews' introduction of Antonio Dominick Benedetti. It was Tony Bennett who walked out and hugged Hope, explaining how much he owed the comedian - for his new name, his career, launched when Bob had put him into his Paramount Theater show in New York years ago. There was enthusiastic applause. Next came Bob's cousins Frank and Kathleen Symons from Hitchin. Other Hope relatives from Hitchin and Letchworth were in the audience. Next came a highly sentimental interlude with the little Anglican priest James Butterworth, known to Hope as "the little Rev," for whom the comedian had done a series of benefits and had raised thousands of pounds to put his war-damaged boys' refuge called Clubland back in business. The audience was effusive. Jack Benny came next. On videotape, because he was opening in Las Vegas that night, Benny said it was "true love" between them.

BENNY: Now, Bob, say something nice about me! Bob?... Bob?... The whole world is waiting...!

The laughter was loud. Then a woman's voice came over the studio sound system.

MILDRED: My mother told me to forget him - he'd never amount to anything.

She walked through the rear double doors and over to Hope who hugged and kissed her. And she was immediately followed by Dolores whose entrance produced applause so enduring that it nearly covered her line.

DOLORES: Don't let them tell you wives can't keep secrets.

In quick succession came British comedians Tommy Trinder and Ted Ray - inserted for home-viewer appeal - and Ray Milland, a long-time pal of Hope's who happened to be in London. Dorothy Lamour appeared on videotape from Honolulu where she was opening a nightclub act with Don Ho. General "Rosy" O'Donnell lauded Hope's USO trouping and then British stronglady Joan Rhodes demonstrated how she had dropped Hope on his head during a USO show in Iceland. Denis Goodwin came in and explained the meaning of NAFT. Then the familiar face with a pipe on videotape, and a voice of mock condescension:

CROSBY: I'd be delighted to lend my stature to assist this - unknown. Exactly what is it that this - Bob Hope - does? What is his talent?

Crosby's appearance was a true audience pleaser. Next came the parade of children, Linda in a dramatic white ballgown; Nora, often considered by insiders as being especially close to her father; Tony, the successful lawyer, boyishly handsome and still in awe of Bob; and Kelly, becoming the show's biggest surprise, the college student who was flown in from Yugoslavia. There was much applause. And the final guest was Mountbatten who said he had come partly to thank "Bob of Burbank" for his appearance on the "Night of Nights."

That was it. When the stage manager signaled an all clear, Andrews thanked the audience and went to escort the other Hope relations seated in the audience to the stage. All the guests stood up and surrounded Hope.

In the Green Room there were hors d'oeuvres and drinks. The party faltered, however, when Mountbatten, guest of honour at the Annenberg reception, and the Hopes, also expected to be special attractions at that gathering, had to say their thank-yous and goodbyes.

Most disappointed when the party limped to what seemed a premature close was Mildred Brod whose other prospect of the evening was the solitude of her Savoy room and hotel food without even a view of the Thames. Someone at the party mentioned that near the Savoy was an excellent place to have a typically English meal but there was no suggestion of companionship.

Mildred tried the recommended roast beefery and was unimpressed. Walking back to the hotel in a cold drizzle she marvelled at coming so many miles to say, "My mother told me to forget him, he'd never amount to anything."

On another occasion when the famous comedian was enjoying being holed up in Frank's tiny house in Hitchin, local milkman Ray Wingate called for his week's money. With such a famous visitor in the house for only a short time, Frank impatiently asked Ray if he could 'leave it for now' as he had Bob Hope visiting. Ray had been handed some intriguing and enterprising excuses by customers wanting to put off paying their milk bill, but this was by far the most remarkable and ingenious, and he was about to say as much - when the great man himself appeared at the door. Full marks to milkman Ray: he'd be happy to delay payment if Bob would have a picture taken with him and his fellow milkman and brother Charles, standing by the Letchworth, Hitchin & District Co-operative Society milk float parked outside. Bob was happy to comply.

That incident happened on one of Bob's earlier visits to Britain, but the story didn't come to light until 1970 when Eamonn Andrews sprang the inevitable surprise on the comedian by opening his famous This Is Your Life book. It was fitting that so many of his British relatives were invited to take part in the tribute, along with such international personalities as Lord Louis Mountbatten and singer Tony Bennett, for given any say in the matter, it would have been just as Bob himself would have wanted it.

Then came Bob's 'surprise' appearance in a special two-part edition of This Is Your Life. Thames Television had been planning the show for about a year and, with the staff of the Savoy Hotel sworn to secrecy, had booked his four children into the hotel where Bob was also staying with Dolores. He had no idea they were there. He had known of the impending "surprise" for some weeks, but when Eamonn Andrews voiced one of the most famous phrases on television, he looked impressively surprised 'Come on,' he drawled. 'You're kidding.' It was a standard Bob Hope phrase.

A whole army of his British relatives enjoyed their moment in the limelight. Earl Mountbatten was there, along with Tony Bennett and an old girlfriend of Bob's from forty years before, and in a television interview screened from America President Nixon said his country was particularly indebted to Britain for giving them Bob Hope, not only for his qualities as an entertainer but also as a man. 'I am proud to know him as a friend,' he declared.

He spent a week in London in November 1970, but got only a brief respite from the political fire. He hosted two benefits for the royal family, including a cabaret show for the World Wildlife Fund that attracted a galaxy of European royalty. ("I'm the only one here who doesn't have his own army," quipped Hope.)

He was the guest of honour for a segment of the British This Is Your Life, with all four Hope children and other relatives and old friends flown in to pay tribute.

TV Times 12 December 1970

Eamonn Andrews substantiated triumphantly his contention that there was still life in the old This is Your Life format by taking the resurrected programme to the No. 1 position in the ratings charts on a dozen occasions.

Andrews confronts Bob Hope with Earl Mountbatten.

Series 11 subjects

Bob Hope | Vidal Sassoon | Talbot Rothwell | Mike and Bernie Winters | Joe Brown | Patrick Campbell | Bobby MooreRobert Soutter | Graham Hill | Sandy Powell | Edward Woodward | Moira Lister | Dickie Henderson | Wilfred Pickles

Kenny Ball | Marjorie Proops | Basil D'Oliveira | Clive Dunn | Peter Noone | Monica Dickens | Jon Pertwee

Lionel Jeffries | Adam Faith | Googie Withers | Matt Busby