Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Bill GRIFFITHS (1920-2012)

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Bill Griffiths, Second World War veteran, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews during a reunion of former prisoners-of-war at the Clive Hotel in Hampstead, London.

Bill, who was born in Blackburn, began his working life as a long-distance lorry driver with the family business. At the outbreak of the Second World War, having joined the Royal Air Force as a truck driver, he was initially posted to Singapore before being transferred to Java due to the Japanese invasion. In February 1942, he was taken prisoner by the Japanese, and shortly after, while clearing ground beneath some camouflage netting, an explosion blinded him and left him without hands.

Although initially given up for dead, Bill was cared for by the medical staff in the prison camp. After the war, he spent time with St Dunstan's rehabilitation centre, where he learnt new skills and slowly rebuilt his life. He set up his own haulage firm and later took up singing and various sports, including swimming and running. In 1969, he was named the Disabled Sports Personality of the Year.

"Good gracious me! No!"

programme details...

- Edition No: 336

- Subject No: 337

- Broadcast date: Wed 22 Nov 1972

- Broadcast time: 7.00-7.30pm

- Recorded: Fri 6 Oct 1972

- Venue: Clive Hotel, Hampstead

- Series: 13

- Edition: 2

on the guest list...

- Alice - wife

- Henry Cooper

- Sheila Scott

- John Edrich

- Terry Neill

- Cliff Morgan

- Edward Dunlop

- Agnes - mother

- Robert - brother

- Alan - brother

- Jim Pennington

- Fred Walton

- Jack Perkins

- Bob Bell

- Harry Simmons

- John Denman

- Hugh Makin

- Alboin Smith

- George Cathercole

- Col Maisey

- Lord Fraser

- Donnie Fee

- Winnie Fee

- Tom Dewhurst

- Barbara Castle

- Mickey de Jonge

- Bob - stepson

- Chris - stepdaughter-in-law

- Shaun - step-grandson

- Kim - step-granddaughter Filmed tributes:

- choir of the Audley Range Church, Blackburn

- Rev Jim Watson

related appearances...

- Lord Brabourne - Oct 1990

- Reg Gutteridge - May 1994

- The Night of 1000 Lives - Jan 2000

production team...

- Researcher: David McFarlane

- Writer: Jack Crawshaw

- Director: Margery Baker

- Producer: Malcolm Morris

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

saluting the armed forces

a celebration of a thousand editions

Bill Griffiths recalls his experience of This Is Your Life in an exclusive interview recorded in October 2009

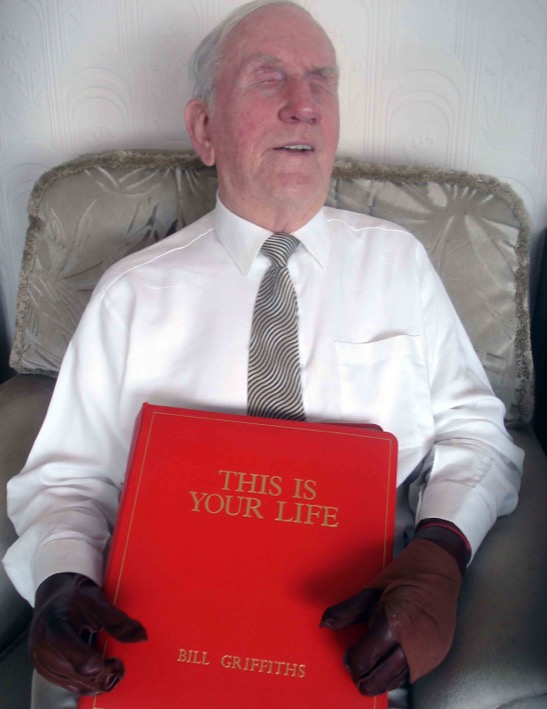

Screenshots of Bill Griffiths This Is Your Life - and Bill Griffiths photographed at his home with his big red book in October 2009

In October 1972, I was invited to give a speech at the London FEPOW annual reunion. We still used to drive to London in those days – we don't any more – and we set off from Blackburn in the morning in pouring rain which turned into a mixture of drizzle and fog by the time we got to Watford, so we were a bit behind schedule when we arrived at St Dunstan's headquarters where we were to stay the night. However, it didn't matter, because the only appointment I had that evening was to meet Harold Payne, the FEPOW National President.

When we'd settled into our room Alice said, 'I must go out and buy some new gloves. I think you should have a bit of a lay down, you look down in, Billy. Do you feel all right?'

'I'm fine,' I said. 'Just a bit tired. I wouldn't mind coming with you.'

'No, you stay and have a rest. I'll not be gone long.'

So off Alice went, and I lay down on the bed and went over my speech in my mind, and maybe I dropped off, because the next thing I knew Alice was back and saying we had to go soon, and she'd arranged for a taxi. I knew she didn't like driving in London, so that didn't surprise me; but I thought she was fussing a bit, making me change my shirt and things, when we were only going to a pub.

Anyway, down we went and the taxi was waiting, and we set off. I, of course, hadn't a clue where he was taking us, and after a bit I wasn't too sure that the driver had either, because he stopped and said, 'Sorry. I think I've gone wrong. I'll have to turn round.'

It seemed to me that he was driving halfway round London, but at last he pulled up and said,

'Here we are.' He opened the door for us, and as Alice took my arm, he added, 'Good luck, sir.' Friendly of him, I thought, but people often feel they should try and say something encouraging when faced with another's disability.

Alice pulled me along, and I thought I felt a tenseness in her which was unusual.

'Are you late?' I asked her.

'Come along, Billy,' she said, and led me down what seemed like a passage, and into a room full of people, all talking. It was very hot and very noisy. Ah, I thought, this must be the bar.

'Can you see Harold?' I asked. Alice didn't reply, but at that moment he came over and said,

'Good to see you, Bill. Like a drink?'

'Very much,' I said.

'Whisky?'

'And a drop of water, Harold, please.'

He went off to get it and I remarked to Alice, 'I can do with that drink. It's dreadfully hot in here.'

At that moment Ted Coffey, the London FEPOW Club Chairman, joined us.

'Hullo, Billy. By the way, I'd like you to meet a friend of mine. Eamonn Andrews, Bill Griffiths.'

Well, I knew that name, in common with most of the population of Britain, and I thought, 'I wonder what he's doing here. Must have popped in for a drink. Perhaps it's his local.' He gripped me by the shoulder and said,

'Very pleased to meet you, Bill. I'm told that you regularly tune in at home to our programme, This Is Your Life.'

'Yes, I do,' I said. 'Very good.' In fact, I'd never much cared for it. I'd always found it a bit embarrassing, tricking some poor bugger into appearing in front of the TV cameras and then facing him with all those people he hadn't seen for years; but I knew it was very popular.

What I didn't know was that the Thames Television cameras had been on Alice and me from the moment we entered the hotel and were on us then, and I still hadn't an idea what was coming next... but I think Alice should take up the story at this point:

Five or six weeks before that evening at the Clive Hotel I had a phone call from our son Bob and his wife asking us over to their place. We went, and when we arrived Chris said she and I were invited to a fashion show at the Keirby Hotel in Burnley. Well, I didn't mind. Bill was happy to stay with Bob and the children, so off we went, just Chris and I. 'What kind of show is it?' I asked her, but she wouldn't say. 'It's all right. You'll see.'

We got to the hotel, and I couldn't see any sign of a show.

'It's all right,' Chris said, and made for the lift.

'It's not all right,' I said. 'What's going on?'

But she wouldn't say, and when we came out of the lift, there were two men waiting for us. They introduced themselves as Jack Crawshaw and David McFarlane, and led us along the corridor and into a private room, where one of them locked the door! I was properly flummoxed. Then the first one, Jack Crawshaw, said, 'Alice – you don't mind if I call you Alice? – would you like a drink?'

'No!' I said, 'not until you tell me what all this is about.' There was a pause. Then Jack said,

'We might as well get to the point right away. We've come to ask your permission for your husband to be the subject of This Is Your Life.'

So that was it. I didn't know what to say.

'Ee,' I said in my broadest Lancashire, 'I don't know, I don't think Billy'd like that at all.'

'Why don't you think he'd like it?'

'To be honest, he doesn't care for the programme. He's often said, "Fancy bringing people on that they haven't met for thirty or forty years and expecting them to remember. It's not fair."'

'What do you think, Chris?' Jack asked her. He'd obviously made an ally of her, for she said to me,

'Go on, Alice. Billy won't mind. He'll enjoy it once he's got over the initial shock.'

I still wasn't a bit sure, but finally they persuaded me, and I accepted that drink. And I needed it, for after a bit of discussion, Jack said,

'Can you promise to keep it an absolute secret? Not to tell anyone except those actually involved? If Billy finds out even ten minutes before the show, it's off. I'm sorry to be so strict, but that's the whole point of the programme. It has to be a complete surprise.'

My mind was in a whirl, and I was already regretting having allowed them to persuade me, for we aren't like an ordinary couple where the man goes off to work, leaving the wife on her own. Billy and I are always together. How on earth was I going to meet the researchers without him knowing? It would be impossible even to use the telephone, and anyway, he always answered it. It was one of the things he could do, like his typing and his tape recorder and his radio, and I'd always encouraged it.

'It'll be very difficult,' I said, but Chris chipped in, 'It will be all right, Alice.'

'That's what you've been saying ever since we left.'

'Jack and David can contact Bobby and me when they want to meet you, and we'll arrange something between us.'

'Oh, very well,' I said. 'I'll do my best.'

'Super,' Jack said. 'We'll be in touch again very soon.'

Whew! What a responsibility! The next few weeks were really dreadful. I just about ran out of excuses for getting away from the house and Billy. Once, when I had to meet Jack and David and I'd told Billy I had a hair appointment, I got back to the house and he sniffed and said, 'You didn't have a hair-do, then?' He's got a nose like a retriever, and he knew at once because he couldn't smell the spray, and I had to lie and say it had been cancelled at the last minute. It was like walking a tightrope with someone standing at one end with an axe, ready to cut it at any moment! Another time, I'd wangled it for Billy to spend the evening with a friend of his because Jack and David wanted to come to our house to get the atmosphere and see all Billy's gadgets. So they came and had a look round and went off, and I thought everything was all right. But the moment he was back in the house he said,

'Who's been smoking?' We'd both given up – or rather, he had, I'd never been a smoker – and he knew at once. He went into his study and said, 'What were they doing in here?' I'd invented some story about a visit from an insurance man, but Billy wasn't happy. He knew at once if things had been moved, which is very important if you're blind. 'Oh,' I said, 'I was busy and he must have just wandered in when I wasn't looking.'

I got away with it, but it was like that for the whole time, right up to the last minute before we left for London. The FEPOW reunion was on the Saturday, and the original idea was for the programme to be done there, but then the producer decided it was going to be too difficult and brought it forward to the Friday, which meant there had to be a reason for us to go to London a day early. Harold Payne, who was in on the secret, rang Billy and suggested they meet on the Friday evening in the Clive Hotel for a drink to discuss the speech Billy was to make at the reunion. When he'd rung off, Billy said to me,

'They're making a lot of fuss about this speech, aren't they? It's only going to last five minutes!'

'Perhaps Harold wants to discuss other things as well,' I said.

'And this Clive Hotel,' Billy said. 'Have a look in the AA Book, Alice, and see if it's in.'

Well, I knew it was a 4-star place, but I pretended to look and said, 'No, it's not there, Billy.'

'Oh, it'll be a pub, I expect. We shan't be there long.'

Little did he know.

I drove down in thick fog – they didn't think to tell me that everyone else was going by train, first class, at the company's expense – and booked us in at St Dunstan's. They wanted me to go to the hotel by myself first for a sort of little rehearsal, and that meant that once again I had to leave Billy. I tell you, I've had about enough of subterfuges and finding excuses to go out by this time, and I was damn sure something was going to go wrong at the last minute. I persuaded Billy that he didn't look too good after the journey and he'd better lie down for a couple of hours while I went out to buy a pair of gloves I needed. He didn't like that, because he enjoys coming shopping with me, likes to sense the atmosphere even though he can't check on what I'm buying! – but he finally agreed, and I told the housekeeper that under no circumstances was he to be disturbed. She didn't like that. 'Billy always had a cup of tea with me in the kitchen,' she said crossly.

'I'm sorry,' I said. 'He's not feeling well and he's to be allowed to rest and not to be disturbed.'

By this time my nerves were in shreds. I took a taxi to the hotel, and Eamonn was there, and Jack and David, and they showed me the set, and how Eamonn would join us in the bar and take us through, and where we were to sit and so on, and I dashed back to St Dunstan's where I now had to persuade Billy that he was quite recovered.

'I don't know,' he said, sitting on the bed half-asleep. 'I don't feel too good, Alice.'

'Come along, Billy,' I said, 'you'll be fine.'

At last I got him up and ready, him grumbling all the time that I was fussing him and why did he have to put on a clean shirt, the one he was wearing was fine, and why was I being so particular brushing his hair over his bald patch when we were simply going round to a pub for a drink, and so on and so forth.

The final thing of all was what I was to wear. I'd been told to put on a long dress, and I knew, a, that Billy would be aware of this as we got into the car, and, b, that he'd want to know why I was wearing a long dress to go to a pub! So I said to him, 'I've forgotten to bring a short dress with me. I've only got the long one for the Festival Hall tomorrow night.'

'Wear that,' Billy says. 'You can get a piece of string and tie it round you and tuck your dress over it!' Honestly, MEN!

A company car came to fetch us. Billy thought it was a taxi with a clueless driver, and we reached the Clive Hotel exactly on time, and with poor Billy not having the faintest notion of what he was in for. What a relief!

'That's great,' Eamonn Andrews was saying, 'because, as your wife Alice knows, we're planning to do a show right now. Tonight, Bill Griffiths, THIS IS YOUR LIFE!'

How many times had I heard that phrase as he introduced someone or other at the start of that famous programme, and friends and relations and long-lost brothers and sisters were all brought in total secrecy for the occasion. But now, as he said the words, 'Bill Griffiths, this is your life' my mind went momentarily blank, and I'm sure my heart missed a couple of beats. I heard Eamonn say, 'Well, we've more surprises in store, Bill...' and I thought, it's a dream, they're having me on, there's been a mistake... but he was saying, 'The cameras are already on us, and in the next room there's an audience waiting. So if you and Alice would care to join me, we'll go through there now,' and I said to myself, keep calm, keep calm! But my pulse was racing, and I felt an air of unreality, as if it was all happening to somebody else. I'm sure that for the first five minutes or so, as I sat on the stage next to Eamonn, I was in a state of shock and I was nervously going over in my mind who on earth they could have rounded up to meet me. I could see it was going to be embarrassing whatever happened – not because I'd anything to hide – how could I have? – but simply trying to remember voices and who they belonged to, and where we'd last met.

Through a sort of mental haze I heard Eamonn say something like '...a life in which, through sheer guts and determination, you've managed to turn tragedy into triumph... people who know the true extent of your courage and achievement... first of all, former European Heavyweight Boxing Champion, Henry Cooper...'

Well, I knew where we'd met, at the Bloomsbury Centre Hotel three years before, when I'd been nominated Sports Personality, and he and Tony Jacklin had pretended to fight over the right to take me back to my seat. Henry said some nice things about me, and gradually I began to relax; perhaps this wasn't going to be so bad after all. But then he wheeled on four other famous sportsmen and women, all of whom I had met, of course, the pilot, Sheila Scott, John Edrich, Terry Neil, and one I knew well, Cliff Morgan, who always did the commentary on the annual Sportsman's Night.

Then I heard Eamonn say '...achievements that could never have been visualised by our next guest when he met you more than thirty years ago... he's flown 12,000 miles from his home in Melbourne, Australia, to meet you again now – Sir Edward Dunlop.'

My goodness, Weary Dunlop, now one of Australia's most outstanding medical men, in demand all over the Far East for his administrative as well as his medical skills, and he'd made time to come to England, just for this programme, the man who'd saved my life not once but twice. I felt quite overwhelmed at the honour, and it was wonderful to be with him again.

Next came my two brothers, Robert and Alan. Robert said a bit about me teaching him to swim in the Leeds-Liverpool canal – Alan never got a word in! – and then Eamonn introduced the swimming team I was in when we won the Bolton Challenge Cup for my school just before I left. There wasn't much for me to do or say except 'My!' and 'Just fancy, after all these years!' and things like that, for I could see it was turning into a kind of 'Bill Griffiths Admiration Society', which was the last thing I wanted. They'd even traced an old RAF mate of mine, Bob Bell, whom I hadn't heard a dickybird from since Singapore; and he told some yarn about a camp concert and me getting so exasperated with a bloke singing 'Beautiful Dreamer' like a donkey with the belly-ache that I went up on stage and tipped him through the window – untrue, of course! However, they then produced the poor lad himself, Harry Simmons, and he started to sing the same thing again, and maybe if there'd been a window handy I might have felt like doing it again!

Eamonn then sketched in the events leading up to the explosion, and brought Weary on again, who said some flattering things about me – '...by his own determination he gave other POWs the will to keep fighting for life, in a situation where lesser human beings would have given up.' And there, in the audience, were half-a-dozen old Java POWs, though I couldn't see them: John Denman, Hugh Makin, Alboin Smith, Col. Maisey, George Cathercole and others, names from a past so distant and awful it seemed as if it had been another life – and there they all were. John Denman I'd kept up with, and one or two of the others, but many I'd almost forgotten until this moment.

And so it went on. Lord Fraser said a bit, then Alice had her turn and talked about our singing, and lo and behold, there were Harry and Winnie Fee who'd set me on the road, and a bit later on, a recording of the choir of Audley Range Church where Alice and I sang, and where we got married. The biggest surprise of all was, in Eamonn's words, '...a very famous lady politician who once came in to meet you and asked to see your telephone...' – Mrs Barbara Castle, at that time our local MP, and the Shadow Minister for Health and Social Security.

It was perfectly true that she had come to our house and asked me to demonstrate how I managed the telephone, and I had dialled a number and said, 'You're through now. It's Mr Edward Heath for you.' She told me the story again now, and it got a good laugh.

The team had persuaded my mother to come down for the programme, as well as Bob, Chris and their two children, now grown up, Shaun and Kim; but they had kept the biggest surprise for last, the woman whose voice had soothed and consoled me during those first awful weeks in Bandoeng, Mickey de Jonge, OBE. How strange and wonderful to hear it again now, without that unending, dreadful pain throbbing in my arms, in a television studio in London where, at that time, I had never expected to be again.

And with that, and Eamonn's final line, 'Bill Griffiths, this is your life', suddenly the show was over. It hadn't, after all, been too bad; and the party afterwards, when I was able to relax and enjoy the company of all the old friends which the programme had gathered together, was great.

For weeks after the show I kept getting letters, many from FEPOW comrades, some of whom I thought had died in prison camp, others from widows of FEPOWs still yearning for information about their husbands, where and how they'd died and so on. I must have received a hundred and fifty such letters, and many of them were very moving, though there was very little I could add to what they already knew. Then there were hundreds of phone calls, most of them friendly and nice, but, human nature being what it is, a number from people who were disappointed at having been left out or were indignant because so-and-so hadn't been included. By and large, though, it had been an exciting and rewarding experience because, as I've said before, the comradeship that was built up as a result of the shared experience of prison camp has been a great strength to me, as to many others – only witness the number who still come to our reunions year after year. It created a spirit which will only die when the last of us has gone.

One thing about that programme which I haven't mentioned was how it came to be put on at all. Some years before, a journalist, Lucia Green, had written an article about me, we had become friends, and she had said that if ever we needed help over publicity or anything, we had only to let her know. Well, it so happened that the Emperor of Japan, Hirohito, was due to pay a state visit to England, and Alice and I thought there should, perhaps, be some reminder of what he'd been responsible for, so I got in touch with Lucia. 'I'll see what I can do,' she said; but instead of writing an article on the subject, she'd gone to Thames TV and put to them the idea of my being the subject of a This Is Your Life programme, which, after much humming and ha-ing, they agreed to. [Geoffrey Pharaoh Adams, another ex-FEPOW says, 'We forgive, but we don't forget'.]

The Times 27 July 2012

RAF lorry driver who was blinded and lost both hands while a Japanese prisoner of war but went on to found his own haulage firm

Courage has many faces. At 21, Billy Griffiths was blinded, severely wounded in the leg and lost both his hands while a Japanese prisoner of war. Unable even to feed himself, there were moments when the burden he imposed on his fellow prisoners became almost unbearable, yet his will to survive prevailed.

An RAF truck driver, he had been evacuated from Singapore before the surrender to the Japanese 25th Army in February 1942 and shipped to Java, only to be taken prisoner on the capitulation of the Dutch East Indies. He received his injuries through the indifference of Japanese guards to their responsibilities for the lives of prisoners of war. Shortly after capture, he was one of about 220 prisoners ordered at bayonet point to clear ground beneath some camouflage netting. The guards stood away as the nets were moved and when Griffiths raised one edge, a violent explosion blinded him, pitted his face with bits of metal, blew off his hands and shattered his right leg.

At the Allied General Hospital, Bandung, run by Commonwealth and Dutch staff under Japanese control, the surgeon - Lieutenant-Colonel (later Sir Edward) "Weary" Dunlop of the Australian Auxiliary Medical Corps - put him on the operating table immediately. After two hours, during which he removed the remains of Griffiths' eyes and tidied the stumps of his arms, he gave his leg only a 30-70 per cent chance of being saved.

The Dutch matron, "Mickey" Borgmann-Brouwer de Jonge, restored Griffiths's will to live despite excruciating pain in the stumps of his arms. Confirmation that his leg would recover helped, as did the care of his fellow patients by feeding him and talking about England. Once able to stand, he forced himself to walk and, on discharge from hospital, two prisoners made him an artificial hand from two tin cans, with which he could feed himself with a spoon and hold a stick to find his way about the camp.

The darkness of three years of captivity, during which his jailers would often mock his disabilities, can only be imagined. Yet release in 1945 brought new grief. Born in Blackburn, Lancashire, where his family ran a haulage business, he had delighted in his job as a lorry driver, married and had a daughter before being called up. He returned to find his wife gone, his daughter in the care of his wife's sister and the business sold.

When his widowed mother found herself unable to care for him at home, he entered the St Dunstan's unit at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Buckinghamshire, where he was reunited with a friend from the Japanese prison camp and met Arthur Cavanagh who, similarly, had lost both eyes and hands, but in North Africa. After training to help to deal with his disabilities, he graduated to Ian Fraser House at Ovingdean on the South Downs, facing the sea. There the director, Air Commodore G. B. Dacre, gave him a fresh perspective by proposing he should set up a new haulage contracting business of his own.

Incredulous of the feasibility of such a prospect, his confidence grew when St Dunstan's provided an expert to teach him business-management and book-keeping. He learnt to type using fittings to his stumps and dial the telephone with his tongue. St Dunstan's offered a loan to buy the first lorry and his two younger brothers joined him.

The lorry was bought, inscribed with "Wm Griffiths" and ceremonially handed over to him by the mayors of Blackburn and Preston in February 1947. The company office was an adapted bedroom in his mother's house and the company gradually made headway until the nationalisation of road haulage forced him to close down at the end of 1949.

Subsequently he met a prewar friend, Alice Jolly, who encouraged him to attend club concerts where she sang and to train his own baritone voice for an amateur competition. As a member of the Far Eastern Prisoners of War Association, he served as an honorary public relations and liaison officer for ten years, took part in sport for the disabled - being voted Disabled Sports Personality of the Year by the Sports Writers' Association of Great Britain in 1969. He appeared on This Is Your Life, hosted by Eamonn Andrews, in 1972. He was appointed MBE for services to the community in 1977. His story, Blind to Misfortune, written with Hugh Popham, was republished by Pen and Sword in 2005.

He married Alice Jolly in 1962. She survives him with his stepson.

William Griffiths, MBE, Second World War veteran, was born on June 26, 1920. He died on July 20, 2012, aged 92

Lancashire Telegraph 6 August 2012

A WAR hero who was blinded and lost both hands during the Second World War, has died aged 92.

Bill Griffiths, who fought with the RAF in Java in 1942, passed away at home in Blackpool with his wife by his side.

At the age of 21, as a prisoner of war, Bill was ordered by the Japanese to uncover a booby-trapped ammunition dump, which left him with his horrific injuries.

After the war, the veteran, who was born in Blackburn, became a leading light for the St Dunstan's charity, which helps blind ex-servicemen and women.

He also wrote books, was named disabled sportsman of the year in 1969 and was also awarded the MBE in 1977. In 1995 he was honored by Blackburn when he was given the civic medal in recognition of his inspiration and example to others.

William Griffiths Court, in Mill Hill, which cares for ex-service people and their families, was also named after him.

Bill's son Bob, who lives in Barnoldswick, said his father had done so much to make the family proud.

He said: "He was very brave, he did some amazing things for his country."

"He used to tour the country, with my mother Alice driving him, speaking for St Dunstan's and raising money for them."

"The whole family are so proud of him. He was very family-orientated and will be sadly missed."

In 1972 he was guest of honour on This Is Your Life, presented by Eamonn Andrews.

Coun Maureen Bateson, who presented Bill with the civic medal, said it had been an honour to know such a 'wonderful gentleman'. She said: "Bill was a really kind and gentle man."

"He was very brave for what he went through. How he survived the war in a prisoner of war camp is just incredible."

"He told such wonderful stories and he was so proud of being honoured by the council."

"Bill was an example of what you can do with courage and how through adversity, you can still do something positive with your life."

"He and his wife are an inspiration to everybody."

Bill leaves his wife, son and two grandchildren.

Series 13 subjects

Pat Phoenix | Bill Griffiths | Shirley Bassey | Warren Mitchell | Dudley Moore | Phyllis Calvert | Larry Grayson | Clive SullivanBill Shankly | Willie Carson | Jack Smethurst | Mary Peters | Noele Gordon | James Corrigan | Pat Reid | Diana Coupland

Dulcie Gray | Janet Adams | Rita Hunter | Leslie Crowther | Jimmy Logan | Spike Milligan | Jackie Pallo

John Gregson | Jackie Charlton | Francis O'Leary