Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Joe LOSS (1909-1990)

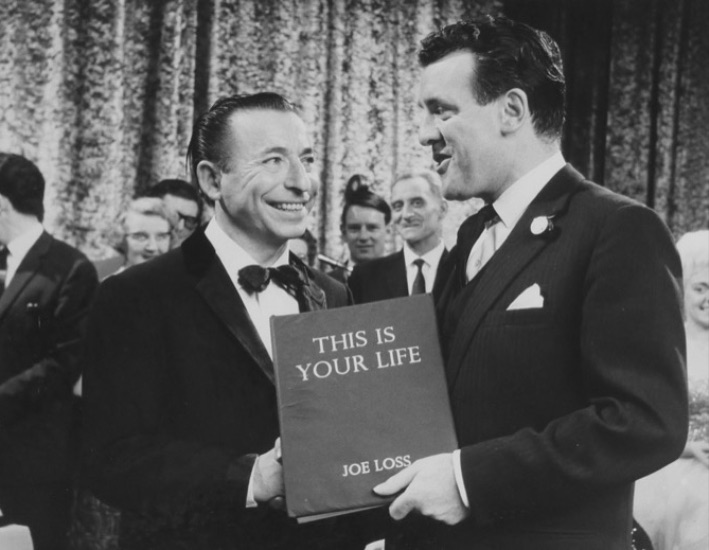

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Joe Loss, musician and band leader, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews while performing at the Hammersmith Palais in London.

Joe, who was born in London and began playing the violin at age five, trained at the London College of Music. He began band-leading in the early 1930s, and by 1934, was topping the bill at the Holborn Empire, leading a twelve-piece band. By 1937, Joe had become the biggest name in the world of big-band music.

The Joe Loss Orchestra was one of the most successful acts of the big band era in the 1940s, creating opportunities for many musicians and singers, and with hits such as In the Mood, which became the band's signature tune. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Joe was the resident band leader at the Hammersmith Palais.

Joe Loss was a subject of This Is Your Life on two occasions - surprised again by Eamonn Andrews in October 1980 at London's Portman Hotel.

programme details...

- Edition No: 225

- Subject No: 226

- Broadcast date: Tue 7 May 1963

- Broadcast time: 7.55-8.25pm

- Recorded: Mon 29 Apr 1963 8.00pm

- Venue: BBC Television Theatre

- Series: 8

- Edition: 30

on the guest list...

- Anthony Hurley

- Fay Saxton

- Nelson Burton

- Mrs Burton

- Harry - brother

- Evie Roffey

- Mildred - wife

- Joe Brannelly

- Jennifer - daughter

- David - son

- Danny Miller

- Monte Rey

- Rose Brennan

- Irene Keeler

- Adelaide Hall

- The Joe Loss Band Filmed tribute:

- Spike Milligan

related appearances...

- Joe Brannelly - Jan 1956

- Vera Lynn - Oct 1957

- Max Bygraves - Oct 1961

- Eamonn Andrews - May 1974

- Ivy Benson - Dec 1976

- Robert Arnott - Dec 1977

- Vera Lynn - Jan 1979

- Bill Waddington - Oct 1986

- Monty Fresco - Nov 1986

- The Story of This Is Your Life - Mar 1987

production team...

- Researcher: Alan Haire

- Writer: Francis Dillon

- Director: Vere Lorrimer

- Producer: T Leslie Jackson

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

- with thanks to Jennifer Jankel and the staff at the Jewish Museum London for their contribution to this page

second tribute

blowing a trumpet for the musicians

surprised again!

a brief biography

the programme's relaunch

The Story of This Is Your Life

a BBC Did You See...? special

Eamonn Andrews - Answers the Question that Everyone Asks Him!

Eamonn Andrews defends his high-profile

TV Times article on Eamonn Andrews

Press coverage of the death and memorial service of Eamonn Andrews

How Eamonn carved a life from insecure beginnings

The Stage reviews the book For Ever and Ever, Eamonn

Jennifer Jankel, daughter of Joe Loss, recalls this edition of This Is Your Life in an exclusive interview recorded in November 2016

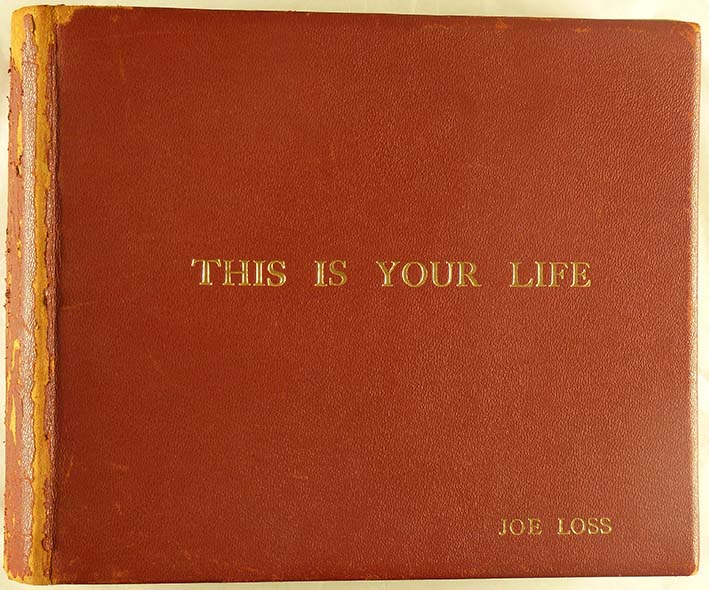

Photographs of Joe Loss This Is Your Life - and a photograph of Joe Loss's big red book

Joe Loss, the popular dance band leader, was also the recipient of the red book on two occasions from Eamonn. Afterwards, he would say, 'It was an unforgettable experience'. Now, as he sat at his desk on the fourth floor of Morley House in Regent Street, he recalled their friendship spanning nearly forty years. When Eamonn first handed him the red book back in the sixties he said he was 'stunned'. 'I think most people in my position go through the same experience – we can't call it anything else. We never think it can happen to us and when it does happen we never expect it. We are shattered.'

On the second occasion, in the early eighties, he reckoned the experience was even more profound. Mildred, his wife, was in on the secret on both occasions and found it increasingly hard to keep it to herself. 'When you've been open with your husband for so long, it's not easy to carry around secrets from him.'

Mildred Loss wasn't surprised when she was approached by the This Is Your Life team for her cooperation. Knowing Eamonn Andrews' affection for her husband, she knew it was only a matter of time before the name Joe Loss would figure in the famous red book.

But she was scarcely prepared for subsequent events. 'They told me that Joe would be surprised by Eamonn at Hammersmith Palais, where he was doing a season,' she recalled. 'Every night as he left the house at 7.30 he'd remark, "I'll see you later, love." His departure was the cue for a BBC researcher to visit me to work out details of the programme. I found the plotting at first rather funny, but after a while I wondered what some of my neighbours must be thinking. I began to feel the strain in case any of them would take Joe aside and ask him if he knew what was going on.'

In fact, the only time he did suspect anything was when he thought his secretary was acting 'strange' and he asked Mildred, 'What's wrong with that woman. Is she looking for another job?'

Eventually she was moved by the programme. 'I think that Joe really felt honoured to be handed the red book by Eamonn. In my own case, I felt a little guilty keeping my big secret from him. We never kept secrets from one another.'

The news that Joe Loss and his orchestra were coming to the Theatre Royal for two weeks pleased Eamonn Andrews. Their music was familiar to him; he had played it regularly on his Radio Eireann programmes, and he liked the big, beaty sound of the orchestra.

Playing the Theatre Royal was nothing new to Joe Loss. He had first encountered audiences there in 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war, and had enjoyed himself. He was to say afterwards, 'Until you worked at the Royal, you didn't know what show business was all about.' He was particularly taken by the enthusiasm of the Sunday night crowds. As he entered the theatre, he saw long queues of people; he knew they were getting value for money because the programme consisted of a variety show, feature film and a quiz.

Earlier that year, 1949, Louis Elliman had invited him to make a return visit to the Theatre Royal. Now, when Louis came to his dressing-room, Joe commented on the great success of Double or Nothing and asked about the compere. 'That's Eamonn Andrews,' Louis said. 'He's very good. He took over from Eddie Byrne.'

Joe Loss came to admire Eamonn's performance. 'He had this rare quality of being able to communicate easily with audiences.' Mildred Loss was also impressed. 'My first impression of Eamonn was that this young man was sweet and charming and loved what he was doing – and the audiences adored him. Like Joe, I enjoyed the quiz. The secret of Eamonn's success as compere was the way he handled the contestants. He wasn't arrogant, he wasn't trying to score off them, no matter how stupid were their answers, and he was adept at putting them at their ease.'

During the run of the show, Joe talked to Mildred about the quiz. 'Isn't it fantastic, love? Don't you think it would be a success in Britain?' His wife was in agreement.

Eamonn's first meeting with Joe Loss was friendly. He was thrilled when Joe and Mildred praised his performance as quiz-master, but was scarcely prepared for Joe's suggestion: 'I've got a proposition, my lad – how would you like to come over to England with the band show?'

Eamonn, who was standing in the middle of the dressing-room, laughed. He thought Joe was joking. He failed to see how Double or Nothing could fit into a top band like Joe's. However, he said quickly he'd love to accept the offer. The idea of working in England with a popular orchestra, appealed to him. While there he would go to Broadcasting House and see if a personal approach was successful; his scores of letters had found no response from BBC chiefs.

By now Eamonn had convinced himself that he had outgrown Radio Eireann, partly because of the frustration and disillusionment he felt every time he suggested new programmes. 'I was up against a brick wall,' he said later. 'The system was beating me.' He knew there were more opportunities in Britain, if only he could make the breakthrough. When he told his parents that he was going to London to work for a while with Joe Loss and his Orchestra, they did not see the point of it. 'Haven't you enough work in Dublin?' his mother said. 'Are you sure you're doing the right thing, Eamonn?'

He regarded the tour as an adventure, though he had to admit that £40 a week wasn't a fortune. His first engagement in England was at the Finsbury Park Empire. He felt nervous about appearing before an English audience, but as he listened to Joe Loss's enthusiastic build-up of the Irish quiz-master it made him feel a little better. He recalled, 'I still trembled in the wings. A build-up is all very well, but the subject of it has to go out there and justify it or duck. At last Joe finished, and I went out on stage and started the quiz. It went well, and it launched me on a hectic breathless tour of one-week dates up and down the length of England, and over the border in Scotland.'

On three consecutive nights a message was conveyed to Joe Loss in his dressing-room that a young comedian wanted to see him about work. Each time he refused to see him. On the fourth night however, he agreed. The young man said his name was Spike Milligan.

'What do you do?' asked Joe.

'I play trumpet, I tell jokes. I'm a bit of an all-rounder.'

'I see... I'll tell you what I'll do. I'm going to give you ten minutes on the show. If you don't get a laugh from the audience you still stay on, and if they go wild for you and the applause never stops, I'll throw you the keys and you can lock up the theatre.'

In a short time, Eamonn and Spike Milligan were buddies. 'I could see that Spike liked Eamonn as a person,' recalled Joe Loss. 'He thought him a genuine fellow.'

It was accepted in the dance band business that Joe 'disliked alcohol around the theatre' and found it hard to tolerate musicians drinking. At the show's interval Eamonn and Spike usually dashed to the nearest public house for a bottle of ale. As Eamonn gulped it down, Spike would say 'Come on, Eamonn, let's get back or Joe will go crazy.'

Joe noticed that Eamonn was popular with the girls. After a show they would crowd around the stage door in the hope of meeting him or getting his autograph. If Joe Loss happened to come out first, they'd say, 'We want Eamonn Andrews.' 'Eamonn, tall and handsome, could have all the girls he wanted,' reflected Joe, 'but he never bothered. I liked him for that, because it meant he was loyal to his girl in Dublin.'

Before he left London, Eamonn went in search of Broadcasting House, and when he eventually located it in Portland Place, he stood in the street and stared at the building thoughtfully. At that moment it represented a challenge to him. 'I tried sauntering in through the high, bronze swing doors, but at the reception desk I was always baulked.' Eventually he got an interview with Tom Chalmers, Head of Light Entertainment, and told him of his ambition to be a broadcaster, he even invited him to come to see him perform with the Joe Loss band show, but Chalmers never found the time to accept the invitation.

Travelling with the band, Eamonn forgot for a while about broadcasting. He became intrigued about the curious lives of the musicians around him, and while he enjoyed their company, he could see they were tough and hard, yet likeable. They tended to be cynical and could name every theatrical digs from Norwich to Dundee, and every nightclub they played. He had fun talking to them. The baby of the band was a quiet little chap called Bill McGuffie, who was a very good pianist and was nicknamed Jose Iturbi. They were characters in their own right, and Eamonn was able to argue with them, or go along with their practical jokes. At night, in digs, he would sit down and write letters to Grainne Bourke in Dublin. He preferred the Irish version of Grace, which was Grainne, and she hadn't objected to his using it.

He was sorry to leave the road show, and although he ended up with less money than when he started, he returned to Dublin happy that he had learned something about show-business in Britain. He would say, 'I was richer by far on the store of experience, but I seemed no closer to becoming any sort of a name on the eastern side of the Irish Sea.'

With his fifteen pounds a week from Double or Nothing at the Theatre Royal, and his income from Radio Eireann, he was again able to give his parents a weekly contribution. He decided not to bombard the BBC any longer with letters; instead, he would wait for a more appropriate opportunity to approach the corporation. After a week at home, the papers carried the news that Stewart MacPherson was leaving England. That same day Eamonn wrote to the BBC stating his experience with Irish radio, and asked to be considered for MacPherson's job as chairman of the radio programme Ignorance Is Bliss.

He was astonished a few days later to receive a reply. They said they were placing his name on a list of people who would be auditioned for the chairmanship of Ignorance Is Bliss.

Series 8 subjects

Rupert Davies | Kenneth Revis | Sydney MacEwan | Cleo Laine | Arthur Baldwin | Edith Sitwell | Ben Fuller | Robert McIntoshMabel Lethbridge | Stephen Behan | Ruby Miller | Richard Attenborough | Daniel Kirkpatrick | Michael Wilson | Dick Hoskin

James Carroll | Uffa Fox | George Cummins | Hattie Jacques | Sam Derry | Finlay Currie | Phyllis Lumley | Ben Lyon | Bertie Tibble

Zena Dare | Victor Willcox | Learie Constantine | Phyllis Holman Richards | Michael Bentine | Joe Loss | Gladys Aylward