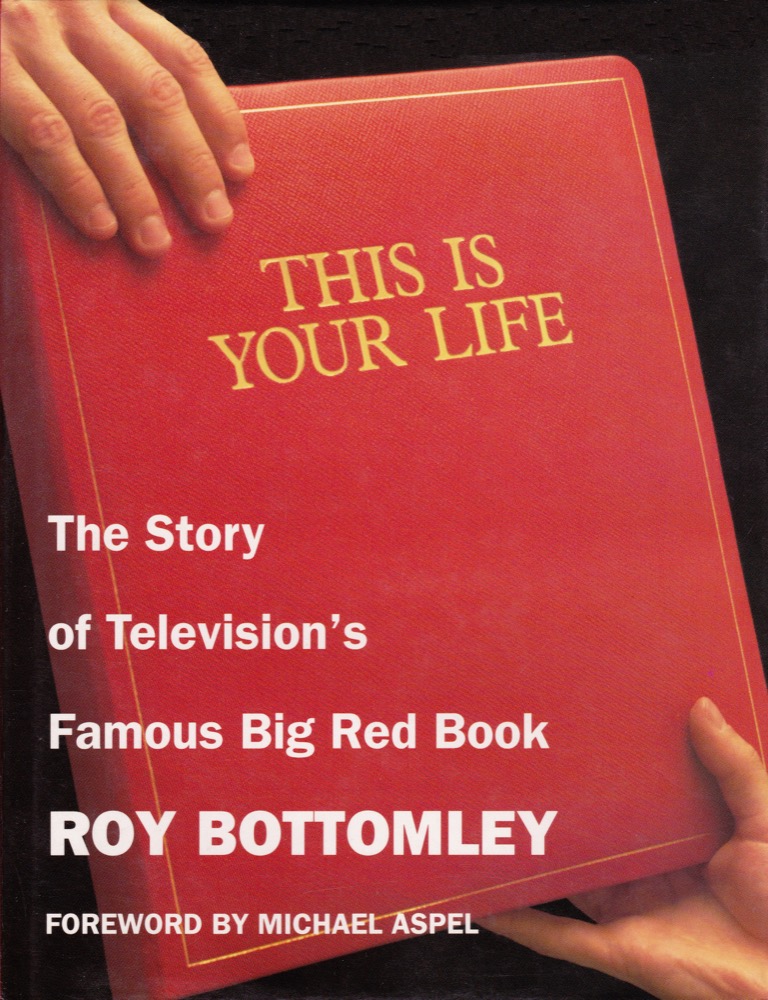

Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Dr Michael WOOD (1918-1987)

- The first 'pick-up' outside of Europe

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Michael Wood, doctor, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews while delivering his Flying Doctor Service in the Bush country of Southern Kenya.

Michael studied medicine at Middlesex Hospital Medical School and, having qualified as a surgeon in 1943, spent the following two years operating on victims of the London Blitz. He left London in 1946 and moved his family and surgical practice to Nairobi, where, having established himself as a General Surgeon, he faced the challenge of efficiently delivering medical treatment to the people of the East African bush country.

While visiting England in 1954, Michael, along with pioneering surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe, and American surgeon Dr Thomas Rees, developed the idea of the African Medical and Research Foundation and its Flying Doctors Service. Having learnt to fly, Michael launched the enterprise in 1959. With a fleet of small planes, the service brought help to millions of Africans, providing medical assistance, surgery, hygiene and preventative medicine to the people of the bush.

"Well, I should fall over backwards... there's a law against hijacking!"

programme details...

- Edition No: 327

- Subject No: 328

- Broadcast date: Wed 22 Mar 1972

- Broadcast time: 7.00-7.30pm

- Recorded: unknown

- Venue: Euston Road Studios

- Series: 12

- Edition: 19

on the guest list...

- Susan - wife

- Katrina - daughter

- Bishop Trevor Huddleston

- Katharine - mother

- Martin - brother

- Frances - half-sister

- Brig Nigel Noble

- Lady Connie McIndoe

- Sister Brigid Corrigan Filmed tributes:

- Dr Hugh De Glanville

- Danieli

- Liz Long

- Bing Crosby

- Hugo - son

- Janet - daughter

- Robin - son-in-law

- Christopher - brother

- Dr Njoroge Mungai

- two unnamed Maasai nomadic warriors

- Chief Mara, Senior Chief of the Maasai Tribal

production team...

- Researchers: Ian Black, David McFarlane

- Writer: John Sandilands

- Director: Margery Baker

- Producer: Malcolm Morris

examining the medical profession

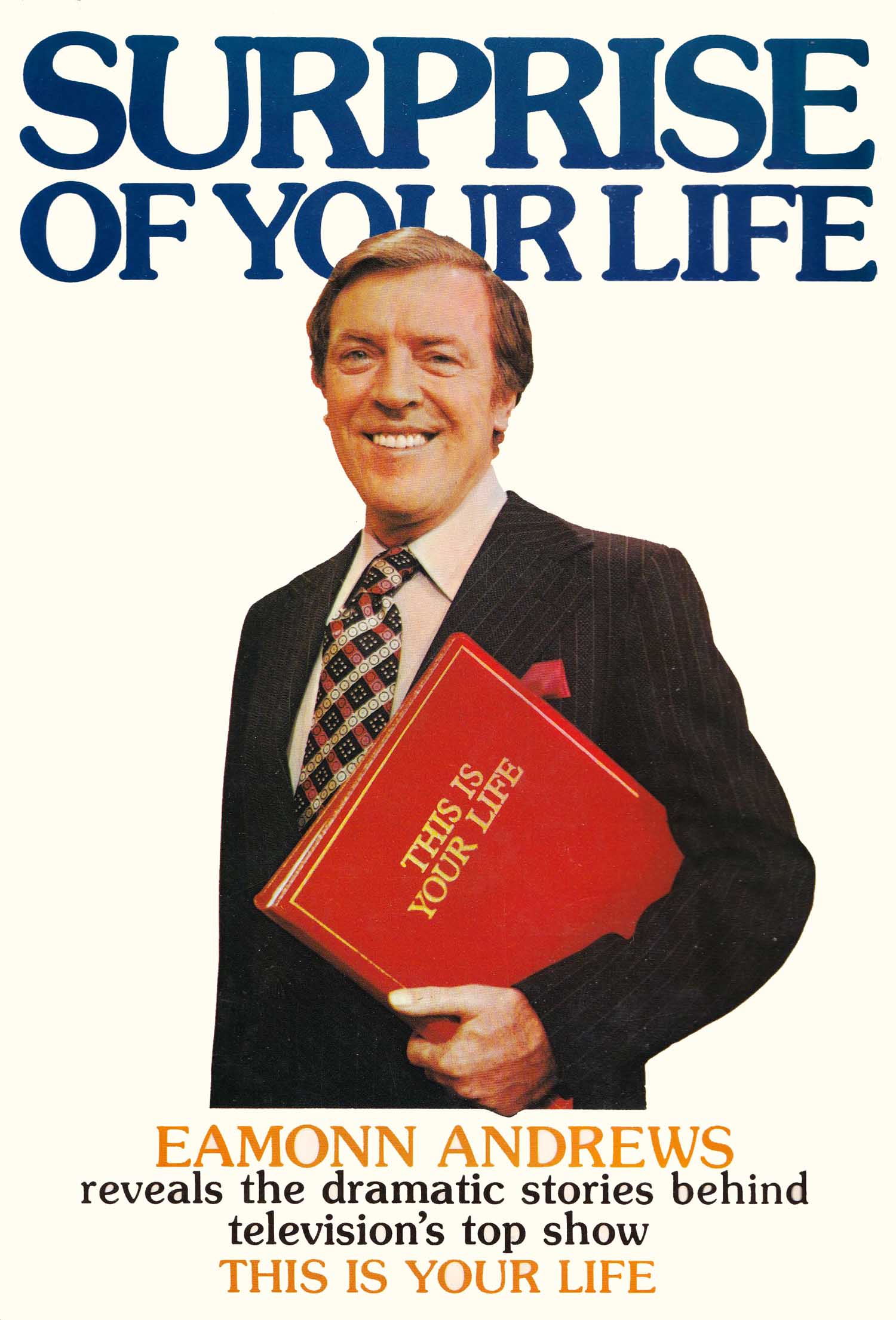

the show's fifty year history

New producer Malcolm Morris reveals more behind-the-scenes secrets

Screenshots of Michael Wood This Is Your Life

This was the most bizarre pick up of all. An idea born at a conference table in a concrete and glass jungle that overlooks the Euston Road. And enacted on a spot in the vast open spaces of the African bush, just a few miles north of the Equator. Bizarre is the word that occurs to me most of all, not just because of all the miles I'd flown. I'd never travelled 4,000 miles just to step off a plane say, for all practical purposes, only seven words and step back on again to fly the same journey back to London. I remember the half smiles that accompanied a kind of excited unreality when the idea was first hatched.

Certainly there was no doubting the strength of the story we were contemplating chasing. Michael Wood was born in a quiet green and leafy countryside of Oxfordshire, an energetic youngster with a lively sense of fun. But what should have been a carefree childhood had been marred by ill health. An inherited asthmatic condition left him virtually an invalid right into his early teens. But his own misfortune only drove him on more and more to achieve his ambition to become a doctor.

Because of his ill health, he had to leave school in England and go to Switzerland. It proved a turning point in his life. His health began to improve and he even took up mountain climbing.

On his return to England he enrolled at the Middlesex Hospital Medical School and qualified as a surgeon at the outbreak of war. Right away he was plunged into the emergency conditions that were to teach him so much that was useful later on when, inspired by the world famous surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe and that legendary expert on Africa Albert Schweitzer, he set up the East African Flying Doctor Service.

Since then he had become something of a legend himself, devoting his life to saving others, indifferent to danger as he flew his light aircraft on mercy missions throughout Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda – always at the ready to fly anywhere medicine was needed. A daring and dramatic life, but often a frustrating one in a part of Africa where superstition had caused many to place their faith and their fear in the witch doctor.

Doctor Wood's territory spanned an area the size of Western Europe. And somehow, somewhere, in that huge expanse of territory we would have to track him down at a time that would make it possible for us to spring our first surprise before flying him back to London with us for the rest of many other surprises.

First to leave England was researcher Ian Black followed later by Margery Baker, Maggi Minchin and writer John Sandilands. It was their job to see if the plans that sounded so grand on paper could be turned into a technical reality out there in the bush.

A few days later I flew out from Heathrow with Malcolm Morris who was at that time my producer. We had arranged to meet our band of latter day Livingstones at an hotel in Nairobi, aptly named The Stanley. The masterplan was to pick up Dr Wood as he flew into a village on one of his regular missions, rush him back to Nairobi, and then take a waiting plane out to London where all the surprise guests were assembling.

When we arrived at the hotel it wasn't difficult to sense the pent-up pressure of it all. Along the corridor from my room I could hear John's typewriter clacking away. There were telephone calls being made to contacts to get us through to certain ministries to get people out of Kenya and to set up meetings with people inside Kenya who knew about the doctor's work at first hand. And all required, as is the way with television, the day before yesterday.

I remember meeting the baffling African wall of silence which I finally translated as some people being too kind to say "No" and managing to vanish so they wouldn't have to pronounce what they might have regarded as a discourtesy. Besides which, red tape is by no means exclusive to Whitehall.

An invaluable contact proved to be an Englishman called Hugh de Glanville, Administrative Director of the East African Flying Doctor Service. He was able to pinpoint the place on the map where we could lay our "ambush".

After a brief and restless sleep I was up early the next morning to join the oddest safari ever. A convoy of Mercedes limousines rough-riding through the bush with yours truly in the back of one of them feeling a touch of embarrassment under the collar of a safari-suit – hired from Moss Bros. But I knew the kit was not just for show as we headed further and further away from Nairobi and into the heart of the bush. When we pulled up at Wilson Airport the natives were being summoned to the village by drumbeat. Some arrived pushing old ladies in wheelbarrows; others had obviously walked miles, ready to welcome the doctor when he arrived to set up his mobile clinic.

It was the moment of truth. Here I was, standing in the middle of a country in which I'd never been before, not quite knowing whether I was in a jungle or a desert and not quite knowing if everything was as peaceful-looking as it seemed.

But most of all I was wondering what this man would say as he came out of the sky. Would he have any idea at all what we were about? Would he have any memory of the programme from his time in England? Would he look at me with a blank expression, thinking that one of the more dangerous cases had escaped and that it was his bounden medical duty to chloroform me quickly and then do a more detailed examination?

Then, as if someone were confirming my madness loud and clear, it began to thunder and the heavens opened with a torrential downpour of warm equatorial rain. Our cameramen and technicians doing their damnedest to look inconspicuous were drenched. But there was no time to look for cover. By coincidence the storm heralded the arrival of the tiny plane carrying Doctor Wood and, by the time it landed and taxied towards us, many of the onlookers had taken what shelter they could.

But not our team. It was now or never.

When he stepped from the plane I was there to present him with the book. When he saw it we were all relieved and flattered that he recognised it. But I still had to do some fast talking to convince him that we were actually serious about taking him back to London with us.

Only when he was assured that his colleague Dr Ann Spoerry, a French born heroine of the air, had agreed to stand in for him did he decide as they say, to come quietly.

Now we faced the problem of getting back to Nairobi, to start trying to get everyone as quickly as we could on to planes to London. I have one abiding memory. Having got Michael down the passageway towards the plane, separated from other people who, unknown to him, were also heading for London, it became clear to me that one person was not going to get out of Nairobi that night. That was Malcolm Morris. As he approached and gave his name he was told by an official that Mr Morris was already on board.

Whatever the reason, all seats were certainly occupied as we took off from Nairobi – with a stranded Malcolm unselfishly deciding that his oddly-assorted flock came first. He would worry about himself afterwards. But it takes more than one setback to keep a good This Is Your Life man down and early the next day he amazed us all by calmly walking into the studios, having flown back via Entebbe and Rome.

The show itself went without a hitch and throughout it I was aware, as we so often are on the programme, of the dedication that surrounded our guest of honour. There was such a sense of unselfishness. There were people with stories just as good, just as praiseworthy, but there was never a hint of it from any of them. Never a suggestion of envy. Never anything but a total giving of their benediction to the man we had chosen. Dr Michael Wood, The Flying Doctor.

A jungle clearing in the African bush was the scene of the pick-up for East Africa's 'Flying Doctor', Dr Michael Wood, in March 1972. Women and children of the Masai tribe anxiously waited for his arrival, and so did Eamonn Andrews and our crew.

Dr Wood had performed an amazing eleven thousand operations in his career. He had qualified as a surgeon at the outbreak of war and quickly became accustomed to dealing with emergencies. Later he was inspired by Albert Schweitzer to form the Flying Doctor service. He had flown his light aircraft over a territory equal in size to Western Europe.

On this particular day his schedule would take him to a village outside Nairobi. The natives were summoned from the bush by drumbeat. Many walked miles to attend the Flying Doctor's mobile surgery.

A sudden cloudburst drenched everybody. Then, as the sky cleared, there was Dr Wood's small aircraft coming in to land. As he stepped from the plane, safari-suited Eamonn was there with the Big Red Book.

It took a while for it to sink in with the doctor that we wanted to fly him from Nairobi to London there and then, a four-thousand-mile hop, where all our surprises were waiting. When he realised we had arranged for another of his team to stand in for him at his mobile surgery he was happy to join us - with someone else at the plane's controls.

We occasionally made a programme outside the studios, if the situation demanded it. Michael Wood worked with the flying doctor service in East Africa. He did such a good job that he became very much a local legend so we decided to devote a programme to his life.

In 1972 my team flew to Nairobi and then travelled for many miles by truck to a Masai village where the doctor was due to land his small plane and hold one of his regular clinics for the villagers. We had arranged for one of his partners to take over the clinic after we threw our surprise. All went well and Eamonn came out from behind some bushes and presented the Red Book to the rather bemused doctor who just stared at Eamonn when he said: 'Michael Wood, this is your life.'

He proved to be a good sport and came back with us to Nairobi airport in order to fly back with us to do the programme back in London. Everything had been arranged, and Eamonn and Michael boarded the plane followed by the crew and finally myself, only I was stopped by the guard who insisted that the plane was now full. Showing him my reserved ticket made no impression because the guard insisted that Mr Morris was already on the plane. As he was carrying a rather large gun and I was getting nowhere, I told the others to go ahead and the plane took off. I then asked if there were any other planes in the airport and they pointed to one on the runway.

'I'll take that one,' I shouted, and ran to the plane, waving my ticket in the air. I got on and the 747 took off. I made my way to an empty seat, waited until we were airborne and called the hostess over.

'Where does this plane go to?' I asked her. Other passengers looked at me strangely.

'Entebbe,' she said.

'And after that?'

'Libya.'

'And after that?'

'Rome'

That was close enough for me. I changed at Rome and much to the surprise of Eamonn and the team, who didn't expect to see me again, I arrived at the studio only six hours late, just in time to make the London end of the programme.

Malcolm Morris, the experienced Thames Life producer, does not like to say that one programme is better than another. 'I find it hard to measure one against the other,' he says. 'In their own way they are almost all totally different because the subjects are themselves different. What I do remember are the exciting moments – like landing by helicopter on a ship for Eamonn's 'pick-up', or when the River Thames traffic was stopped for twenty minutes to surprise a subject. These are the moments that make the programme such an exciting experience.' Eamonn, on the same subject, would say, 'I never compare one programme with another. I think this would be fatal. To me the moment of the hour is the most stimulating.'

On reflection, though, Malcolm Morris felt one of the programmes he liked to remember best concerned the English doctor, Michael Wood. He flew to Kenya with Eamonn and planned to surprise Dr Wood as he flew into a village on one of his mercy missions, then drive him back to Nairobi, and that evening fly him to London where he would be met by the Life guests.

Both producer Morris and Eamonn considered Dr Wood's story one of the most fascinating they had encountered for some time. A big, burly man, with receding grey hair, he had been troubled in his youth by an asthmatic condition, but when he was sent to school in Switzerland his health improved greatly. On his return to England he qualified as a surgeon. Later, he decided to follow in the footsteps of the legendary Albert Schweitzer and devote his life to the welfare of Africans. In the course of his mission work he flew thousands of miles across Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

'The idea of surprising Dr Wood in the African bush intrigued Eamonn,' recalls Morris. It would become his most unusual 'pick-up'. On arriving in Nairobi he and Eamonn joined members of the Life team in their hotel. As they studied the map, it looked more like a military operation than a This Is Your Life story. Eamonn was to notice a pressure among the team, mainly because of the elaborate arrangements to be made to fly Dr Wood back to London. They encountered the usual red tape but eventually smoothed out the arrangements, so that everything now depended on Eamonn to make a successful 'pick up'. But where? It took some time before the precise area in the bush was pinpointed. It was a weary Eamonn who finally retired to bed, more hopeful than confident that the mission would succeed.

As he would say, he experienced a restless night's sleep. Next morning with Malcolm Morris and the Life team, he set out on safari. 'It was the oddest safari ever,' he would say later. 'A convoy of Mercedes limousines rough-riding through the bush. I felt somewhat embarrassed under the collar of a safari suit - hired from Moss Bros. But I knew the kit was not just for show as we headed further and further away from Nairobi and into the heart of the bush. When we pulled up at Wilson Airport the natives were being summoned to the village by drumbeat. Some arrived pushing old ladies in wheelbarrows; others had obviously walked miles, ready to welcome the doctor when he arrived to set up his mobile clinic.'

It was the first time that Eamonn had travelled 4,000 miles to surprise a subject. To Malcolm Morris, it was a very exciting moment as he watched Eamonn prepare for the pick-up. But Eamonn was nervous. He was in unknown territory. How would the busy doctor react? He began to worry. All kinds of disturbing questions ran through his mind: 'Would Dr Wood have any idea at all what we were about? Would he have any memory of the programme from his time in England? Would he look at me with a blank expression, thinking that one of the more dangerous cases had escaped and that it was his medical duty to chloroform me quickly and then to do a more detailed examination?'

Suddenly, it began to pour with rain, and in the distance came the sound of thunder. The Life crew were drenched. A few moments later a small plane descended out of the sky and slowly taxied to a halt on the ground. It was the cue for Eamonn to move forward and present the red book to Dr Wood. Eamonn recalled, 'When he saw it we were all relieved and flattered that he recognised it. But I still had to do some talking to convince him that we were actually serious about taking him back to London with us.'

As if there was not enough excitement for one day, Malcolm Morris eventually found there was no seat for him in the plane back to London. However, he was able to grab a seat on a plane that would take him via Entebbe to Rome and on to London. Even Eamonn was amazed to find his producer the next day at his desk at Thames.

It was a Life programme that afforded Eamonn immense satisfaction. Not only did it manage to grip the viewers, but the whole operation had gone without a hitch. To Malcolm Morris, it was a story of courage and hope and adventure. It was the kind of Life programme that brought the very best out of Eamonn, for he happened to admire people like Dr Michael Wood, The Flying Doctor.

Series 12 subjects

George Best | Alfred Marks | Rolf Harris | Don Whillans | Sacha Distel | Les Dawson | Doris Hare | Keith Michell | David FrostBarry John | Michael Flanders | Charlie Williams | Ginette Spanier | Hughie Green | Tom Courtenay | Hylda Baker

Gordon Banks | Alan Rudkin | Michael Wood | Graham Kerr | Pauline Collins | Ray Illingworth

Patricia Hayes | Nosher Powell | Richard Briers | Lulu