Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

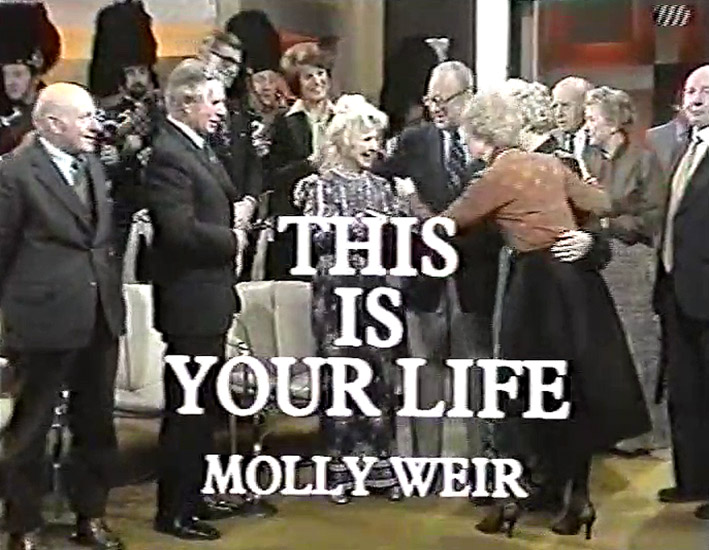

Molly WEIR (1910-2004)

THIS IS YOUR LIFE – Molly Weir, actress, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at Euston Station in London, having been led to believe she was there to be filmed for the Scottish Tourist Board.

Molly, who was born in Glasgow, became the shorthand champion of Britain, with 300 words per minute, after studying at secretarial college. She joined the amateur dramatic Pantheon Club while working as a secretary before success in the Carroll Levis Discoveries Show prompted her to turn professional.

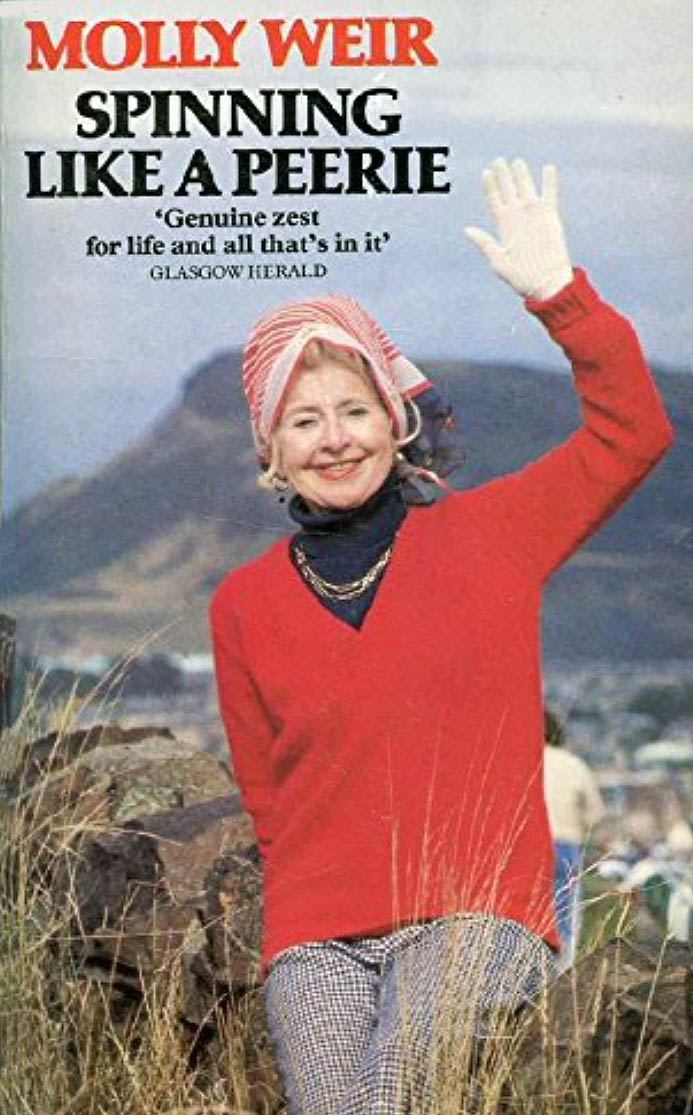

Regular appearances as Tattie McIntosh in the wartime BBC radio show ITMA led to her moving to London, where she achieved wider national fame as Aggie in another BBC radio show, Life with the Lyons. She later appeared on television, notably in the ITV drama series Within These Walls and published several books.

"Oh, Eamonn! It's not! Oh crikey!"

programme details...

- Edition No: 455

- Subject No: 452

- Broadcast live: Wed 2 Feb 1977

- Broadcast time: 7.00-7.30pm

- Venue: Euston Road Studios

- Series: 17

- Edition: 15

- Code name: Flood

on the guest list...

- Sandy Hamilton - husband

- Tom Weir - brother

- Isa Sutherland

- Janet Brown

- Willie Joss

- Jack House

- Ruby Duncan

- Moultrie Kelsall

- Deryck Guyler

- Moira Anderson

- The Caledonian Highlanders Pipe and Drum Band

- Ben Lyon Filmed tribute:

- Tony Martin

related appearances...

- Ben Lyon - Mar 1963

- Deryck Guyler - Jan 1974

- Stuart Henry - Nov 1983

- The Night of 1000 Lives - Jan 2000

production team...

- Researcher: Maurice Leonard

- Writer: John Sandilands

- Directors: Royston Mayoh, Terry Yarwood

- Producer: Jack Crawshaw

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

spotlight on the stars

a celebration of a thousand editions

TV Times photo feature

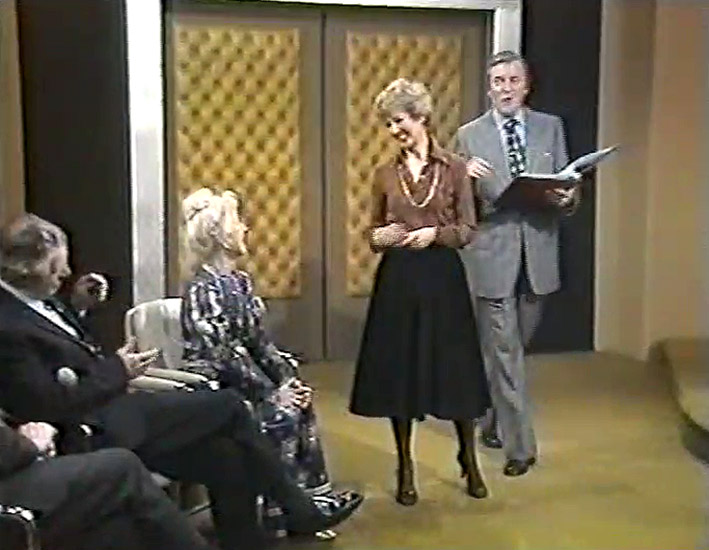

Screenshots of Molly Weir This Is Your Life

One day the telephone rang and it was my agent to see what I was doing in February, round about the first or second of the month, or possibly even the end of January. She always had to check with me, because as well as my acting performances, which were booked through her, she knew I had dates for Associated Speakers and with Flash. I looked at my diary and said that as far as I could see, there was only a possible Flash commercial which could always be rearranged if they knew early enough. It appeared that the Scottish Tourist Board wanted me to go up to Scotland in May, to make a film to promote tourism for them, but at this stage they merely wished to check if I was free, if I was interested, and if I would be prepared to do an opening shot for them either at the end of January or early February, showing me leaving from Euston Station. Because Euston was a working station, they had to take whatever date was most convenient for them, and it was suggested by British Rail that January or early February would be best. We would just pretend this was me leaving in the merry month of May, for inside a station nobody would know what time of the year it was.

I was agog with excitement. Putting my hand over the mouthpiece, I said to Sandy, who was hovering by the kitchen door, 'Sandy, they want me to go up to Scotland in May, isn't that great? You come too, and we'll have a holiday out of it, for my fares will have been paid.' Always the prudent Scot, I seize the chance of a holiday the moment somebody pays my fares to any enticing location.

My agent came back again, having checked her own diary, and told me that she would be in touch with the firm date later. She couldn't say exactly where I was going to do the filming in Scotland; all that would be arranged in good time. It was merely the preliminary shot from Euston they were concerned about, so that they could go ahead and make their plans with the Railway authorities.

That winter, Sandy seemed much more content to whizz about on his own, doing the shopping, disappearing for hours to the library, and cycling far afield for fruit bargains. He even went into town one day and bought himself a dinner suit at a sale in Moss Bros. I was quite bemused, for normally he likes me to hand out a bit of advice when he's buying major items like this, but when I offered to go with him, he said, 'No, no, I'll manage fine. You get on with the book, that's far more important.'

So I settled down to the writing, and was amazed to find what a surprising amount of time I was able to devote to this book, without having the slightest feeling of guilt that Sandy was finding time hanging heavy on his hands.

My agent rang again within a week or two to tell me that the date had been definitely fixed for 2 February. I was reminded to wear clothes appropriate to the merry month of May. Nobody looking at the finished film would guess that the shot of my departure had been done months before. The important thing was to look suitably summery when I was filmed getting off the train in Scotland at the other end, when it would actually be May. I wondered how I was going to disguise my red nose on a freezing February day in lightweight skirt, a jacket you could have 'spat peas' through, and fine shoes. I decided I'd take my cape along to keep my legs warm, even though they'd said they would send a car.

It was bitterly cold and there was a fall of snow in the morning. When I looked out of the window, I said to Sandy, 'I think I'll ring the Tourist people and tell them I'll go in by train. It's far more reliable than risking being held up on snowy roads.' 'Och, I wouldn't do that,' said Sandy. 'The train might be held up, and they wouldn't know where you were. Just you take the chance of a comfortable warm ride into London.'

'Och aye, you're quite right,' I said. 'I'll let them do the worrying, and it's only a short sequence after all. It shouldn't take long.'

I spent the whole morning in the gazebo, writing, and was slightly irritated by the way Sandy kept hovering around, asking me when I'd be coming in for lunch, what I'd be wearing on my feet, and whether I wanted to take perfume and make-up with me.

'Sandy,' I said, 'a quarter to one will be time enough to come in. They're not coming with the car till two o'clock and I want to delay as long as possible taking off these warm trousers.' I sighed slightly impatiently, 'And of course I don't need to take perfume with me. I've got it on, and it'll surely last for the hour I'll be at Euston.'

That's what I thought!

When I was ready, Sandy suddenly decided to inspect my shoes, and gave it as his opinion that my flatties weren't very elegant to travel into London with a movie director. 'Sandy,' I said, 'they'll not see my feet. It's my head and shoulders they're interested in, I'm just to be seen waving from the carriage windows.' I had put warm insoles into the flat shoes, and nothing was going to part me from their comfort on this icy day. Just try on your court shoes,' Sandy coaxed, 'I think they look nicer with your suit.' To humour him, I put them on, privately amazed at the interest he was taking in this quite small engagement. 'Far nicer,' he beamed. 'I'd wear those if I were you.' 'All right,' I said, 'but I'm going to wear the insoles with them even if they cripple me.'

I found there was just time to varnish my nails, and Sandy flew back and forward to the front window like a hen on a hot girdle watching for the car. 'Sit down and keep warm,' I said. 'The man will ring the bell, and he'll just have to wait till my nails dry anyway.' I was just at my pinkie when the bell rang, and on the doorstep stood a tall man in a white suit, looking every inch a movie director. 'Will these clothes do?' I asked him, after he'd introduced himself as Maurice George. 'Will they look right for the later shot showing me getting off the train in May?' He hardly even glanced at them, and me 'chittering' with cold just to please him. 'Yes, yes,' he said, 'they're fine.'

I turned to Sandy, 'Just take the tripe out of the fridge about four o'clock,' I said, 'I'll cook it when I get back. I should be home about half-past-five at the latest.' I turned to the Tourist Board man, 'It won't take longer than that, will it?' 'No,' he said, 'that should be all right.'

He was most attentive. When I wanted the car stopped to drop some letters into a pillar-box, he seized them and posted them for me. Again, when I asked if I could drop some letters into the BBC when we were passing, thriftily taking the chance of saving about a dozen stamps, he wouldn't let me budge out of the car, but leaped out and did this little task himself. 'Nice man,' I thought, 'typical filming spoiling!'

We chatted about writing, about books, and of course about the film, and I was slightly surprised that he didn't seem to be too certain about exactly what poses we'd strike when we actually got down to taking the pictures at Euston. For I now discovered that it was 'stills' we were taking, and it was not a filmed sequence at all.

'But why do we have to go to Euston to take still photographs?' I asked. And then, before he could answer, I said, 'Oh of course, where else could we find an inter-city train but in a station?' I make life very easy for deceivers!

To my delight, he suggested that as we were a bit early for the railway people, we should go and have some tea. We actually went into the newly refurbished Ritz. The Ritz, indeed! This was spoiling with a vengeance. Even as I was preparing for an orgy of cucumber sandwiches, we were told we were too early for tea. They didn't start serving for another hour, so we headed for a French patisserie where I devoured a huge chocolate meringue, and made a fine old mess of my lips and teeth, and drank a whole pot of tea.

It was the last bite of food I was to enjoy for two whole days, I may say.

We reached Euston at exactly 3.55 p.m. We were due at four o'clock.

My word,' I said, 'you're very exact. Suppose the car had been held up?'

We went through the ticket barrier with the words, 'We're the Scottish Tourist Board,' and were nodded past. This made me laugh. 'I like our cheek', I said. 'Just the two of us. We are the Scottish Tourist Board.'

As we strolled down the ramp, I saw a crowd standing at the bottom. 'Oh,' I said with some excitement, 'the Queen must be coming. There's a crowd gathered down there.' Never for one moment did I think that that crowd had anything to do with me.

Then, to the right of the ramp, near the crowd, I spotted a pipe band. 'Oh,' I said, 'maybe she's come from Balmoral'.

The next moment, as I wondered why the director wasn't pushing through the crowd to reach the train for our photography session, lights blazed, there was a skirl of the pipes, and from somewhere, like a Jack-in-the-box, out jumped Eamonn Andrews with the famous red book, and said, 'MOLLY WEIR, THIS IS YOUR LIFE'.

'But I'm here to do a film for the Scottish Tourist Board,' I said indignantly, and I turned to the big director who had brought me. 'Will you ever forgive me?' he said.

My stomach turned over, my legs turned to jelly, and I realised this big man was all part of the plot.

I covered my face with my hands, and said, 'Oh Eamonn. Oh crikey!'

Then in sudden awareness, I said, 'Am I not going to Scotland in May at all?' The man shook his head.

'And there's no Scottish Tourist job?' I asked.

Again a shake of the head.

It was such a disorientated feeling, that I was pulverised and my mind became a complete blank.

I was whisked away to a hotel with the big man, but I have no recollection of how we got there. By this time I was shaking so much and felt so sick with fright that I had to ask for my ever-reliable Phosferine tablets. I could have had practically anything else in the way of food, drink or sustenance, but not a Phosferine tablet was there in the entire place. In desperation I searched through my purse, found a 'stoury' squashed one which had been there for weeks, and washed that under the tap and then sucked it feverishly to see if it would give me some strength, and control of my shaking limbs.

Then a thousand questions. 'What about clothes? Oh can I ring Sandy? He'll die of fright if you spring this on him for he won't know anything about it, Can I ring my sister-in-law?'

'No, you can't ring anybody.'

I was persuaded to take a tiny drop of champagne and nibble at a sandwich, and then, with my teeth still chattering with shock, was taken by car to the Thames studios.

I was smuggled through a side entrance, passed from hand to hand, and locked into a make-up room. When the girl saw my hair was long, she said, 'Oh I can't do long hair very well. Would you like to do it yourself?'

It was at exactly that moment that I decided the whole thing was simply a very vivid dream. It all fitted. Make-up girls didn't suggest you did your own hair. They loved doing hair. That was what they were paid for. And nobody kept champagne on ice in make-up rooms, except in dreams. Why was there no tea, but plenty of champagne? They didn't even have an elastic band for my topknot of hair. In a make-up room in the heart of London! Of course, I was dreaming.

There was no doubt about it.

The clothes which were hanging up confirmed it. There was my long dress. There was also a top but no long skirt. There was a tiny short petticoat. And there was a fur coat. And gold shoes. And an odd belt. It had all the daft irrelevancies of a state of dreaming, and suddenly I became as calm as a cucumber and thought I must remember as much of it as possible so I could tell Sandy when I wakened up.

Until Sandy walked on to that TV stage, I didn't know that he had been in the plot since Christmas. I could not believe it. I would never have thought him capable of acting such a part for so long.

Later, much later, those mysterious telephone calls, the disappearances to 'get the paper', or 'go to the library', fell into place. When there is perfect trust, there is no suspicion. But it wasn't deceit on his part, he was just keeping a confidence. He told me later he absolutely hated it, and at times he couldn't believe that I could be so naive, and so unquestioning. I've always said I would be the easiest person in the world to kidnap, for I never believe anyone would do me any harm, and if a car arrives for me I step into it, confident I will be taken where I am supposed to be going.

I always said, too, that I would never do a This Is Your Life, for I was far too emotional and would be in floods of tears from start to finish. In the event, I never shed a tear, for I was too caught up in my dream.

Another of the things I 'always said' was that I would never be caught, for I would know at once if anything was phoney. And I was well and truly caught. They couldn't have thought up a better trap if they'd thought for a hundred years. For, having already done work for the Scottish Tourist Board, and having a long-standing love affair with trains, it seemed the most natural thing in the world to be asked to take part in a film for them, and to be photographed in a railway station.

The rest of the show, and the party, and the pipers, were unforgettable.

Those who know my volatile temperament were amazed when they looked in and saw how happy and composed I was. They couldn't know that the shock had been so complete that it had frozen all my normal emotions, and I had given myself up to my vivid dream.

How else could I have leaped up in front of an audience of over nine million and sung a song I hadn't thought of for years, without giving a thought that I might not remember a word?

How else could I have remembered without the slightest hesitation the names of people I hadn't seen for years?

How else accepted the fact that my brother Tommy disappeared from the scene afterwards without a word to me? Actually he had had to fly back to Scotland for his own TV filming the next morning, but I didn't even question the reason for his leaving.

The pipers came to the party, and we danced and we sang, and I did a Highland Fling, and played the drums. The whole thing was the most exciting madness.

And then, suddenly, the dream was going on too long. I felt exhausted and said, 'I want to go home.'

A car arrived, and Sandy collected the flowers and the champagne, and we dropped Rose and Tom off at Charing Cross Station, and we went home.

Sandy had arranged tickets for them to be in the audience, but I questioned nothing at that time. I was coasting along with the very tiring dream still.

It was only when we reached our own house and the telephone started ringing after midnight, and we read the notes which were lying in the hall from the neighbours, that I wakened up, and realised with a dazed sense of shock that it had all actually happened.

It wasn't a dream. I had really seen all those friends and colleagues. Willie Joss, and Jack House from Glasgow. My brother Tommy. Moultrie Kelsall and Ruby Duncan from Edinburgh. Janet Brown and Moira Anderson. Deryck Guyler. And Ben, my old boss Ben Lyon, all the way from Hollywood. Isa from Springburn. How did she get there? Where had she stayed?

I never slept a wink all night. Each time I was on the point of drifting off, I re-lived that frightening moment when Eamonn Andrews had leaped out at me with the big red book, and I shot up wide awake, as if I'd been hit over the head with it.

All next day I talked and talked, trying to unwind. Things I had never noticed at the time suddenly became significant. Sandy's interest in my shoes, for of course he knew I'd be seen full-length walking down that ramp towards the cameras. His persuasiveness that I ought to let them take me by car while I had the chance, and not change my plans and go by train. He said that when he told Eamonn this during their rehearsal, Eamonn had said, 'Thank God nobody told me. It would have ruined everything.' The director's lack of interest in my clothes, and his keeping me safely in that car until he could deliver me at the right spot at just the right time. Those 'wrong' numbers when I would pick up the telephone - they had been from Thames of course. My agent's confusion when I answered the telephone one day when she had expected me to be out. I had changed my hair appointment without telling Sandy! Sandy's insistence that he bought the dinner suit without taking me to town! That had been the day, he told me, when he had met the man I knew as Maurice George (he was really Maurice Leonard) to hand over some photographs. It all made sense bit by bit, and I wondered how I could have been so blind.

Next day the letters started coming. Scores of them. People wrote whom we hadn't heard from for years. The telephone went non-stop. There were the telegrams and the bouquets and the poems. There were even letters from dozens of people who hadn't seen the show, apologising for having missed it, and wondering if I could possibly have it repeated!

The common theme of many of the letters was that the writer had just been on the point of going out, or hadn't had the TV switched on, and that the telephone had rung umpteen times, with the voices of friends shouting down the 'phone, 'Molly's on - switch on This Is Your Life,' before banging down the receiver. One of the funniest was from a vicar to whose parish my dear old Blackpool landlady had retired. Olive and her sisters had taken good care of me when I was in Blackpool with Life With the Lyons, and now she lived alone. The vicar knew I kept in touch with her, and what a valued friendship ours was. He had been out delivering the church magazines that evening when suddenly, waiting at the door of one house, he heard Eamonn's voice announcing the famous words, 'Molly Weir - This Is Your Life'. He told me he simply threw the magazine in his hand through the open door, picked up his cassock, and ran non-stop through the village street and catapulted right into Olive's sitting room. Before she could draw breath to ask what was the matter, he had switched on the TV, and they both watched the show to the end, without a word being spoken. He was out of breath anyway, and Olive was speechless with joy in meeting on television all my friends and family. She especially loved seeing Ben Lyon again, for she was a great fan, and she was thrilled they had brought him all that way to be on my programme.

It was the top show nationwide that week, and it won the Bouquet of Roses from the Sunday Mail, a bouquet awarded by the readers and viewers by popular vote.

It was the most staggering thing that had ever happened to me in a life packed with challenges and surprises, and I thanked the good Lord from the bottom of my heart that it could not happen twice. I could never again be so lucky to be protected from making a fool of myself with tears and terror, because of my absolute certainty that I was dreaming. It was a wonderful accolade, but it was also the most tremendous shock, and it took me a long long time before I could eat or sleep properly.

Series 17 subjects

Frankie Howerd | Wilfred Hyde-White | John Blashford-Snell | Mervyn Davies | Pam Ayres | Ivy Benson | Jim WicksJoss Ackland | John Inman | Patrick Cargill | Sheila Hancock | Tom O'Connor | Florence Priest | Tony Britton | Molly Weir

Anthony Quayle | Alfred Pavey | Michael Denison | Mary Chipperfield | Leonard Sachs | Cyril Fletcher | Matt Monro

Tony Greig | John Frost | Brian Rix | Alberto Semprini | Louis Mountbatten