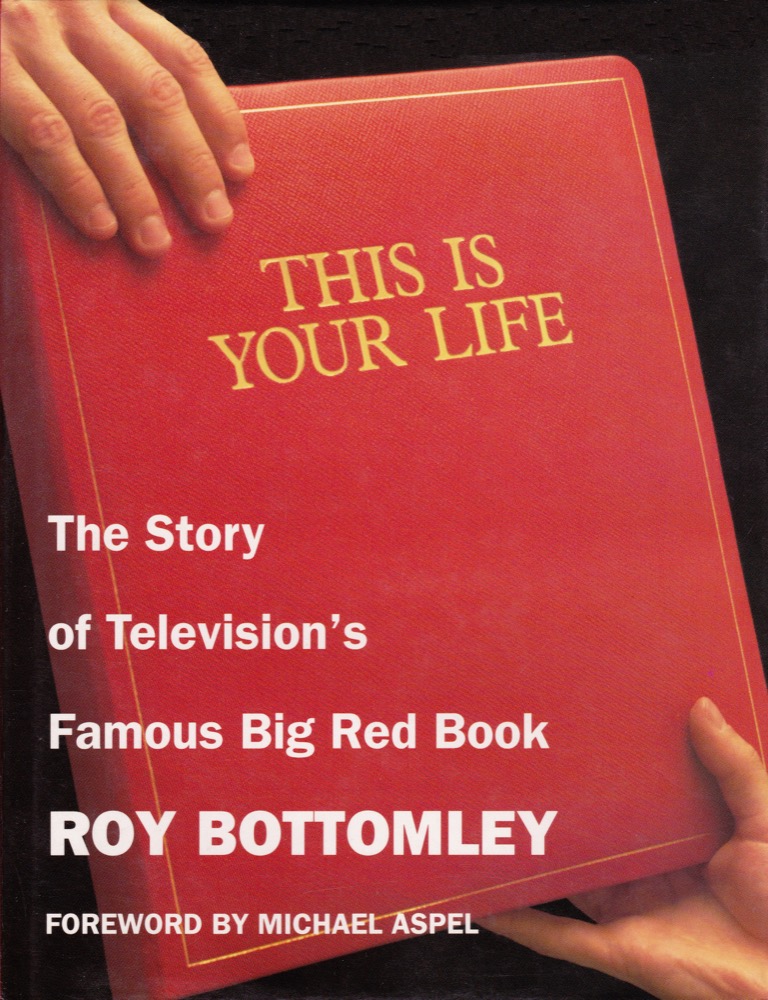

Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Alan WHICKER (1925-2013)

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Alan Whicker, journalist and broadcaster, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews during a press reception for his newly published book at the Berkeley Hotel in Knightsbridge, London.

Alan, who was born in Cairo, Egypt, but grew up in Richmond, Surrey, worked as a newspaper reporter before serving with the British Army during the Second World War. As an officer in the Devonshire Regiment of the Army's Film and Photo Unit, he led a team covering the action in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. After the war, Alan worked as a foreign correspondent for the Exchange Telegraph News Agency.

He joined the BBC in 1957 and became an international reporter for the corporation's Tonight programme, presenting a segment called Whicker's World, which later became a huge ratings success as a fully-fledged series in itself in the 1960s and 1970s and brought him worldwide acclaim with his distinctively jaunty presenting style of subtle satire and social commentary.

"Now listen, you know I've got a word for everything – but not tonight – this can't be true!"

programme details...

- Edition No: 597

- Subject No: 594

- Broadcast date: Wed 17 Mar 1982

- Broadcast time: 7.00-7.30pm

- Recorded: Mon 8 Mar 1982

- Venue: Royalty Theatre

- Series: 22

- Edition: 24

- Code name: Bamboo

on the guest list...

- Valerie Kleeman - partner

- members of the Alan Whicker Appreciation Society

- Harry Hamilton

- Dick Gade

- Richard Hughes

- Cliff Michelmore

- Jenny Michelmore

- Guy Michelmore

- Jack Gold

- Cyril Moorhead

- Baroness Fiona Thyssen

- Huw Wheldon

- Trevor Philpott Filmed tribute:

- Jackie Stewart

related appearances...

- Leslie Thomas - Jan 1979

- Noel Barber - Dec 1979

- Joe Loss - Oct 1980

- Cliff Michelmore and Jean Metcalfe - Dec 1986

- Lord Brabourne - Oct 1990

- Ned Sherrin - Feb 1995

- Jeremy Clarkson - Oct 1996

- Lord Deedes - Dec 1998

- The Night of 1000 Lives - Jan 2000

production team...

- Researchers: John Graham, Vivien Lind

- Writers: Tom Brennand, Roy Bottomley

- Directors: Paul Stewart Laing, Terry Yarwood

- Producer: Jack Crawshaw

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

celebrating the hosts

a celebration of a thousand editions

TV Times looks at some 'unplanned' incidents

Screenshots of Alan Whicker This Is Your Life

Richard Hughes, the Rabelaisian Australian correspondent, had been widowed and was managing the Tokyo Press Club in the Shinbun Alley when we met. There were side benefits, even forty years ago: $80 a week, plus free board and half-price drinks. This was considered a good deal, though not good enough to halt the move to Hong Kong, as Japanese domestic prices climbed out of sight.

Dick was large and Pickwickian – though financially closer to Micawber. He called our ultra-casual club "Alcoholics Synonymous". When in Hong Kong, a dozen or more of us would meet upstairs at Jimmy's Kitchen in Central, or in the Grill Room at the Hilton where a bust of Dick presided over his usual table. Those found worthy were appointed "Hatmen", because if a message should arrive warning that any one of us was in trouble, the reaction would be instant: "Gimme me hat." This imperative recalled Dick's Australian origin. (I fear the call to arms may be too late for some of us...)

War correspondents go through a lot of life and death together, and the Korean War was dangerous and exciting enough. In Fleet Street I might run into a friend who shared my jeep for a few treacherous days before Pyongyang – and we'd pick up the conversation mid-sentence. Such a close relationship was fired in danger, though rarely survived a home posting.

After the war, in true Hatman tradition, Dick dropped everything and flew to London to say kind things on my This Is Your Life programme, recalling the moment I was reported – with some exaggeration – shot down and killed on the Korean front.

The first time I saw Dick after my brush with the North Korean artillery was when I entered the Radio Tokyo press centre on my way back from Korea, to learn that I was a ghost. "My God," he whispered, "you're dead." There's a limited number of replies to that.

To support this disturbing news he showed me the story he had just filed detailing the whole unhappy incident, supported by two (very short) pieces on the front pages of the Daily Mail. They recorded the death in action of yet another Allied correspondent, followed by a Reuter's obit. That seemed to settle the matter. I was a statistic – and so young.

In fact the Royal Artillery in Korea had that morning put up two Piper Cubs as aerial observation posts over the front line. On my way back to Kimpo and on to Tokyo, I was offered a hot seat in a Piper Cub, and was too cowardly to refuse. So, teeth clenched, I was spotting targets in the plane that was not shot down.

Some years later, when I was surprised by Eamonn Andrews and various friends and colleagues, Dick came on stage to explain my fatal crash, quite easily: "The front page story in the Daily Mail said he'd been lost in action, and we presumed the press can't be wrong. It gave us an admirable excuse to sink a few drinks and to toast one of our friends – a great reporter and great interviewer who proved once again what our mutual friend Ian Fleming said, 'You're only as good as your friends.'"

I did not instantly recognise myself, until Dick was followed on stage by Huw Wheldon, then the BBC's Controller of Television. He continued the flattery – sort of – by telling Eamonn, "He's a magnificent journalist and a first-rate television reporter, but the really interesting thing about Alan is that he looks like an inquisitor, he looks stern, but in fact he's got a heart of gold. He's kind and benevolent – people actually like him."

"But those terrible glasses, that accusatory countenance and mordant turn of phrase, that grated voice that says, 'Don't you dare lie to me!' Yet he is in fact good-humoured and lets people speak for themselves. He has no victims, only friends – everybody loves him."

Twenty-five years of television journalism, two million miles of travel under his blazer, an opinion poll saying the majority of people would love his job, and the press launch of his book Within Whicker's World – 8 March 1982 was perfect timing to surprise the vintage broadcaster still travelling well.

Starting on his local newspaper at five shillings a week, working with Montgomery for the Army Film and Television Unit in North Africa during the war, then joining the Exchange Telegraph agency, Alan Whicker had put in some tough groundwork on his glittering career, including covering the Korean War.

Veteran Sunday Times Far East correspondent Richard Hughes flew in to tell us how surprised his colleagues were when he walked into the press HQ in Tokyo during the Korean War. The Daily Mail had reported Whicker 'lost in action'.

He started his television career as a freelance for the Tonight programme, and BBC colleagues Cliff Michelmore, director Jack Gold, Sir Huw Wheldon and Trevor Philpott were all there to pay tribute. Reflecting Whicker's fascination with the rich and famous, the wife of one of the world's wealthiest men, former Vogue model Baroness Fiona Thyssen flew in specially.

Whicker had won BAFTA's 1977 Richard Dimbleby Award. But he remained convinced that when he freelanced for Tonight there was a behind-the-scenes conspiracy to send him anywhere in the world where it was raining.

Series 22 subjects

Bob Champion | Bill Fraser | Wayne Sleep | Ian Botham | Cannon and Ball | Rob Buckman | Angela RipponJulia McKenzie | Jackie Milburn | Paul Shane | Peter Adamson | Kiri Te Kanawa | Mickie Most | Anita Harris

Mike Brace | Faith Brown | Robin Bailey | Rod Hull | Bob Monkhouse | John Toshack | Wally Herbert

Joe Gormley | Roger Whittaker | Alan Whicker | Peter Davison | Douglas Bader