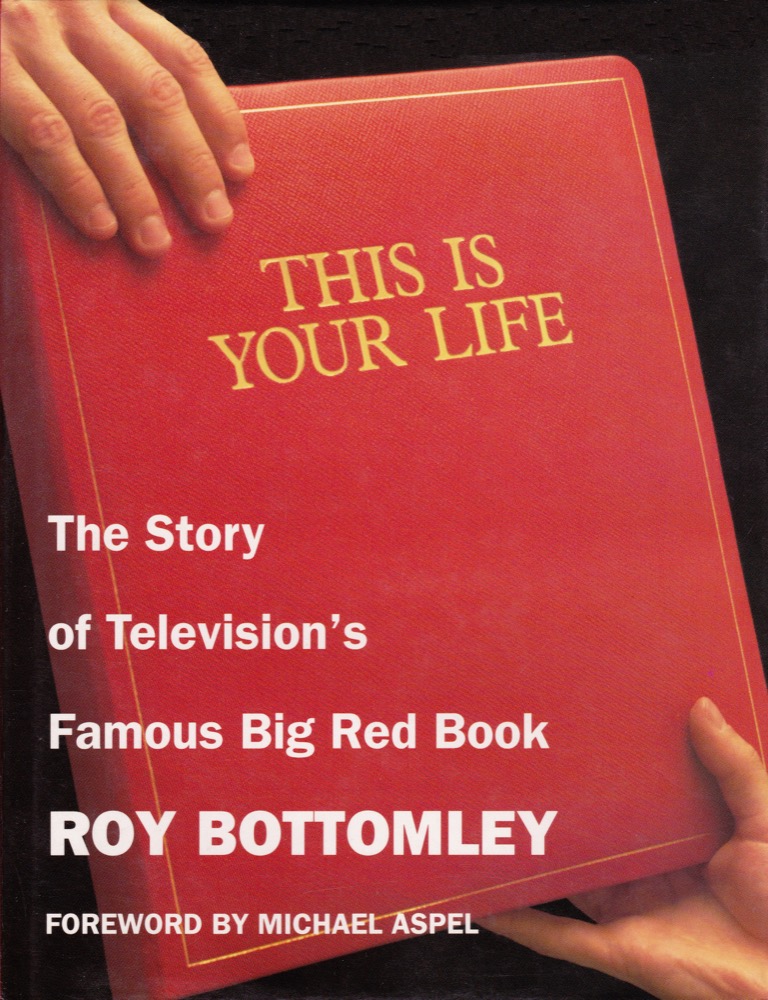

Big Red Book

Celebrating television's This Is Your Life

Group Captain Sir Douglas BADER CBE, DSO, DFC, FRAeS, DL (1910-1982)

THIS IS YOUR LIFE - Douglas Bader, Royal Air Force flying ace, was surprised by Eamonn Andrews while presenting a cheque for £50,000 to the children's charity SPARKS during a reception on the Martini Terrace of New Zealand House in London's Haymarket.

Douglas, who was born in London, studied at St Edward's School in Oxford and the Royal Air Force College in Cranwell, where he was a keen sportsman. Having been commissioned into the RAF, he crashed his aeroplane in December 1931 while attempting some aerobatics and, as a result, lost both his legs. He was discharged from the RAF against his will and found work with the Shell Oil Company. At the outbreak of the Second World War, Douglas, having proved he could still fly, rejoined the RAF, scored his first victories over Dunkirk during the Battle of France in 1940, and later took part in the Battle of Britain.

In August 1941, Douglas baled out over German-occupied France and was captured. Despite his disability, he made several failed escape attempts and was eventually imprisoned at Colditz Castle. After the war, Douglas was promoted to Group Captain but left the RAF permanently in February 1946. He resumed his career in the oil industry while continuing to campaign and fundraise on behalf of many groups and charities. The book Reach for the Sky, which chronicled his RAF career, was adapted into an award-winning film in 1956.

programme details...

- Edition No: 599

- Subject No: 596

- Broadcast date: Wed 31 Mar 1982

- Broadcast time: 8.00-9.00pm

- Recorded: Tue 2 Mar 1982

- Venue: Royalty Theatre

- Series: 22

- Edition: 26

- Code name: Reach

on the guest list...

- Roy Kinnear

- Bill Pertwee

- Reg Varney

- Bernard Cribbins

- Bob Wilson

- Joan - wife

- Jane - stepdaughter

- Gary - stepson-in-law

- Wendy - stepdaughter

- David - stepson-in-law

- Michael - stepson

- Sue - cousin

- Clare Hoare

- Laddie Lucas

- Jill Lucas

- Robert Hunt

- Walter Dingwall

- Angela Douglas

- message from Kenneth More

- AVM Joe Cox

- Eric Sykes

- Alan Minter

- Henry Cooper

- Dickie Henderson

- Tony Jacklin

- Bobby Locke

- Bernard West

- Tubby Mayes

- Noel Barlow

- AM Sir Denis Crowley Milling

- ACM Sir Harry Broadhurst

- Hugh Dundas

- Alan Smith

- Johnnie Johnson

- Geoff West

- Adolf Galland

- Al Deere

- Lucille Glaneux

- David Lubbock

- Robert Stanford Tuck

- Col Philip Bardow

- Lord Linlithgow

- Joan Hargreaves

- Gamie Rees

- Jonkheer John H Loudon

- Chief Jim Shotbothsides

- Rosaline Shotbothsides

- Wing Cdr Paddy Barthropp

- John Mills

- letter from HRH Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother

- The Central Band of The Royal Air Force Filmed tributes:

- Charley - grandson

- Adam - grandson

- James Stewart

- Vera Lynn

- Madame Petit

- Madame Hiecque

- Philip Hartley and family

- Michael Ellis-Smith

- Margaret Ellis-Smith

- Clare Ellis-Smith

- Paul Ellis-Smith

- Nellie Wallpole

related appearances...

- David Butler - Mar 1962

- Eric Sykes - Dec 1979

production team...

- Researchers: John Graham, Vivien Lind

- Writers: Tom Brennand, Roy Bottomley

- Directors: Paul Stewart Laing, Terry Yarwood

- Producer: Jack Crawshaw

- names above in bold indicate subjects of This Is Your Life

saluting the armed forces

the special editions

the producers who steered the programme's success

The Guardian obituary for the former This Is Your Life director

Screenshots of Douglas Bader This Is Your Life

On 2 March 1982, Douglas was present at a cocktail party at the Martini Terrace in London's Haymarket, arranged for people who had raised thousands of pounds for handicapped children. Just after Douglas handed over a cheque for £50,000 generated by the fund-raising group 'Sparks', of which he was president, to Action Research for the Crippled Child, the legless celebrity and knight was 'ambushed' by TV presenter Eamonn Andrews.

After weeks of careful research, throughout which time his family had steadfastly maintained secrecy, it was the turn of Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader on the long-running Thames Television series This Is Your Life. Back at the Royalty Theatre, Douglas was soon meeting family and friends, all of whom paid glowing tribute to the man whose story Andrews described as defying 'fiction' as an example of 'soul-stirring heroism'.

Old Walter Dingwall from St Edward's appeared and even Madame Hiecque was filmed speaking from her bed. Better still, onto the stage walked Lucille Debacker herself – visibly moving 'Le Colonel'. Among the wartime luminaries was Dogsbody Section – Johnson, Smith, West and Dundas. The latter said, 'So long as Douglas Bader was there, morale was always sky-high... two words describe Douglas Bader: bloody marvellous!' General Adolf Galland appeared, British film legend Sir John Mills, boxing champion Henry Cooper, all paid tribute – as did the indomitable Nellie Wallpole and Paul Ellis-Smith from their respective homes.

Sadly, Kenneth More was suffering from Parkinson's disease and was unable to attend. Instead the actor who had become the cinematic face of Douglas Bader was represented by his wife, Angela Douglas, who read this message: 'My dear Douglas, you know very well why I can't be with you this evening. More the pity! But I'm sending my old lady along to represent me. She's been in love with you for years anyway! Your inspiration and courage is, quite rightly, a legend. It was with me through the film and is with me still.'

The most impressive tribute came from Clarence House: 'During the dark days of the Second World War, those of you who served in the Allied Forces brought hope and confidence, skill and determination. In times of peace you have been an inspiration to the young, and have given encouragement and support to many who have suffered physical misfortune. I send this evening my greetings and warmest good wishes for health and happiness in the years ahead. Elizabeth R, Queen Mother.'

As the entirely positive and sympathetic programme concluded, Andrews presented Sir Douglas with his commemorative red album, as the Central Band of the RAF struck up rousing martial aviation music. Sadly, however, there would not be 'years ahead' but mere months.

Reach For The Sky was the film of the best-selling book based on the life of Group Captain Sir Douglas Bader CBE, DSO, DFC, a true story beyond the reach of any writer's pure invention. Said Eamonn Andrews outside New Zealand House just before the pick-up: 'Tonight, I hope to pay tribute to one of the greatest romantic heroes this country has known, this century or any other.'

It was Tuesday 2 March 1982, and sixteen floors above where Eamonn waited for the lift to the Martini Terrace, many famous names had gathered to witness Sir Douglas hand over a cheque for £50,000 to Action Research for the Crippled Child. All had been involved with SPARKS, the star-studded fund-raising organisation.

Few could be more qualified to hand over the cheque than the pilot who, with artificial limbs, became one of – in Churchill's immortal description – 'the Few'. The few to whom so many owed so much in the Battle of Britain.

'This story defies fiction,' said Eamonn, and it did. Our cameras saw the cheque handed over, then Eamonn made his way through the celebrity crowd to produce the book.

Researcher on the programme was John Graham, now associate producer, who discovered that Bader was such a brilliant sportsman he had been selected from the RAF rugby union team for the full England squad – until a fateful day, 14 December 1931.

The young pilot was visiting an aero club near Reading. He went for a 'spin' and crash-landed. His legs were mangled. His log-book read, 'Bad show.'

Laddie Lucas, his fighter-pilot pal who married the sister of Bader's wife Joan, told me he later questioned Bader on what had happened.

'Just made a balls of it, old boy. That's all there was to it.'

Kenneth More was the perfect casting to play Bader in the film Reach For The Sky. They became firm friends. Alas, on the night we surprised Sir Douglas, Kenneth was not well enough to join us. He was, in fact, as we learned later, suffering from Parkinson's Disease and did not have long to live.

His wife, actress Angela Douglas, came to the Royalty Theatre from where we presented the programme, with a moving message from Kenneth More. 'Your inspiration and courage is, quite rightly, a legend. It was with me all through the film and is with me still.' At that time, the Parkinson's still a secret, not many realised the profundity of that simple message.

Even without legs, Bader was not to be put off his sport, taking up golf and getting down to a handicap of just four; he could justly claim to top the crack of the late Sammy Davis Junior who, when asked his handicap, replied, 'I'm a one-eyed Jewish negro, what more do you want?' At least Sammy had legs.

Douglas Bader's accident meant he had to be retired from the RAF, but when Hitler invaded Poland he was among the first to volunteer to get back into the cockpit of a Hurricane or a Spitfire.

He proved to the RAF powers-that-be that he could still fly and, after Dunkirk, was appointed Squadron Leader at 242 Squadron at Coltishall, East Anglia. France had fallen. 'The Few' took to the skies and the Battle of Britain began. In one dog-fight a bullet ripped through Bader's Hurricane instrument panel, tearing away a cloth chewing-gum bag strung around his neck.

Air Marshall Sir Denis Crowley-Milling (then a humble pilot) told the packed Royalty Theatre (and twenty million viewers) about Bader going to the pictures on a rare night off. In the darkness, he stumbled on a step and called to an astonished usherette, 'I've damaged my blasted leg. Fetch me a screwdriver.' He got it, fixed the joint in his artificial knee-cap, and said to the open-mouthed usherette, 'Thank you very much.'

By 1941 he was flying two sorties a day, alongside heroes such as Air-Vice-Marshal 'Johnnie' Johnson, later a Life subject.

Bader's luck could not hold out much longer and, when the rear half of his Spitfire was torn away in mid-combat collision, he thought this must be the end. Not so. As he attempted to bale out, his leg was trapped in the fuselage and ripped away. The irony was that had it not been an artificial limb, Bader would have hurtled to certain death in the crashing Spitfire.

He landed safely, and was captured by the Germans. The Commander of the famous JG 26 Fighter Wing was so impressed with this daredevil RAF pilot with no legs that he offered him a close look at the plane he'd been firing at, the Messerschmidt 109. That same Commander, General Adolph Galland, flew in to tell us that Bader's first request was to take the 109 for a spin around the airfield. 'It was clear what was in his mind,' smiled the German air ace.

When in 1945, General Galland was himself taken prisoner, Bader gave him a box of cigars. 'A formidable enemy, but even better friend,' said the man who survived many a dog-fight with Douglas Bader.

It was Galland who agreed to a request from Bader that a new pair of artificial limbs be dropped by parachute to him. Equipped with new 'legs' and knowing he was due to be transferred to Colditz, Bader escaped from the hospital wing of the POW camp. We flew in the French nurse who helped him – and many others – in that escape. Like the elderly woman – ninety-eight when we did the programme, but still able to film for us – who hid Bader and the others, she was discovered and sent to a concentration camp.

Sir Douglas greeted the nurse, Lucille Glaneux, with gratitude and affection the years had not diminished. Proudly she wore her French Resistance medals, including the Croix de Guerre for 'supreme bravery'.

Our audience rose to its feet in tumultuous applause, and not a few tears.

Bader was recaptured and tried tunnelling out of the next prison camp by hiding the soil in his artificial limbs. Then, when he was trying to escape, with others, through the wire, a German guard smashed the butt of his rifle down on the foot of the nearest would-be escapee. He could not understand it when Bader burst out laughing. It was his foot.

He tried to get out of Colditz with a party of laundry workers, but failed when a guard tapped his legs and was greeted with a hollow 'clunk'.

Sir John Mills told us how Bader became the only man to stand before the Queen to be knighted. And the Queen Mother sent a letter to be read out on the programme, thanking Sir Douglas for his 'courage in war and inspiration in peace.'

When the band of the Royal Air Force entered from the rear of the stalls to march down the aisles playing the famous 'March Past', there was not, as we say, a dry eye in the house.

Or the nation.

Series 22 subjects

Bob Champion | Bill Fraser | Wayne Sleep | Ian Botham | Cannon and Ball | Rob Buckman | Angela RipponJulia McKenzie | Jackie Milburn | Paul Shane | Peter Adamson | Kiri Te Kanawa | Mickie Most | Anita Harris

Mike Brace | Faith Brown | Robin Bailey | Rod Hull | Bob Monkhouse | John Toshack | Wally Herbert

Joe Gormley | Roger Whittaker | Alan Whicker | Peter Davison | Douglas Bader